I first read Post-Dated at 30,000 feet; Boston to SFO. By coincidence, the man sitting next to me was reading Thoreau’s Walden, a book usually confined to students and scholars (and everyone else’s bookshelves). He was well past his student years and turned out to be an engineer who simply loved Thoreau.

I bring this up because Post-Dated has a chapter titled: Restless Spirits: The Usefulness of Henry and Ernest. Henry is, of course, Henry Thoreau. Ernest is Ernest Hemmingway. Michael included them in his book because they both studied bonsai in Japan as young men. Henry was gifted, but Ernest was too impatient to get very far with bonsai, though his reputation as a person who could consume rivers of sake, while telling spell binding stories of bullfights, lost lovers and big fish, is still alive and well in Japan (now, after apologizing to our readers (both of you) and especially to Michael Hagedorn, let’s see if we can refocus).

I loved Post-Dated. Unlike any other bonsai book I’ve ever read (including mine), it’s a genuine page turner. Michael’s gift for story telling, and his sense of humor (mostly at his own expense) are as strong as his gift for bonsai. Here’s a sample:

“I had studied Japanese for a full year before arriving in Japan, and in every class I had attempted, there was a faint halo of a dunce cap sitting on my head. The brain had ossified in my thirties, seemingly unwilling to assimilate anything new of this sort. The difficulties continued while in Japan, where one would think constant verbal exposure would soften this mental geology. This was a conversation in Japanese, at teatime, going over a bit of studio inventory: I comment: “We have long onions and short onions, but no medium ones.”They stare at me, wordless, The conversation continues and leaves me far behind,mulling over long and short onions.“SCREWS! Not onions, screws! Sorry!”

Just the funny and embarrassing stories would make your time and money well spent. But there’s plenty more; including numerous observations for anyone interested in how cultures take different approaches to life’s issue, big and small: “Tachi (another apprentice) got a lecture today from Mr. Suzuki, again, a drilling about placement of branches and arrangement of shoots. I sensed the tension although I was in and out with various tasks …. The next day Mr. Suzuki took me aside and said that he is very hard on Tachi to strengthen his spirit, that it is difficult to have a weak one in this business… I do not envy the expectations that lead to a lifetime of stress in Japan. In the U.S. we allow life itself to temper the spirit; in Japan, your teacher does it. Up to the age of thirty Japanese are considered tamago, eggs, and teachers are expected to break their students open, and prod their insides.”

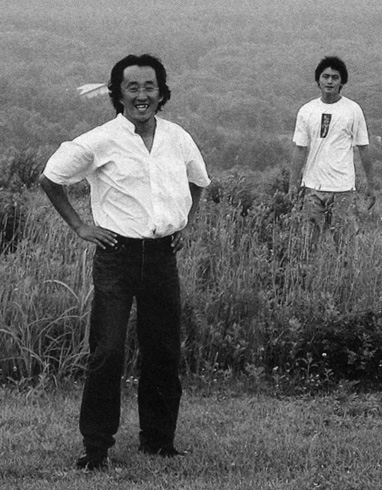

Mr. Shinji Suzuki, foreground, and his other apprentice, Tachi.

Mr. Shinji Suzuki, foreground, and his other apprentice, Tachi.

As you might expect, bonsai stories are woven throughout, with valuable lessons in the Japanese way of bonsai (which, though some Westerners feel is overly concerned with detail, really works; the proof being in the pudding). Here’s one of many:

“In the prepared pot, I poured a half inch of granular soil, and he (Mr. Suzuki) chastised me, “Dame!” (pronounced dah-may) Not good! “This maple is old and has thin twigs, so don’t add the chunky soil to the bottom. Finer soil. Dame! “

When I read this, a light went on in my all-too-often thick-skulled head and I remembered something I once knew. Aha! That explains why some old bonsai mavens use finely screened, small particle shohin soil on their older fully developed trees. Fine soil equals fine roots. Fine roots support fine twigs. Of course!

As reread this, I don’t feel I’m doing Michael Hagedorn and Post-Dated much justice. There’s a bigger story that Michael captures and communicates so well. It’s about life as an apprentice in a baffling and sometimes wonderful world, and beyond that what is real and unreal in this human realm where people stumble along, styling beautiful bonsai while sticking both feet in their mouths and then sharing the outrageousness of it all with humility (not far from humiliation), honesty, and best of all, a great sense of humor.

PS. There really is a chapter about Thoreau and Hemmingway, and the man next to me really was reading Walden. Now, you may not be so impressed with this, but seriously, when was last time that you and the person next to you were both reading about Thoreau and one of you was reading a book about bonsai?

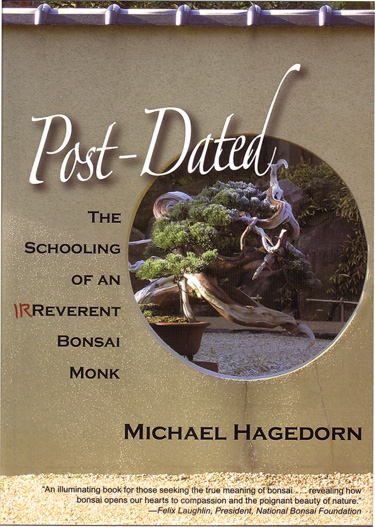

Post-Dated: The Schooling of an Irreverent Bonsai Monk

By Michael Hagedorn

Crataegus Books, Portland Oregon

Softcover, 216 pages, $14.95

This book is a must-have! I’m thinking of giving it to my mom who is a bonsai lover.