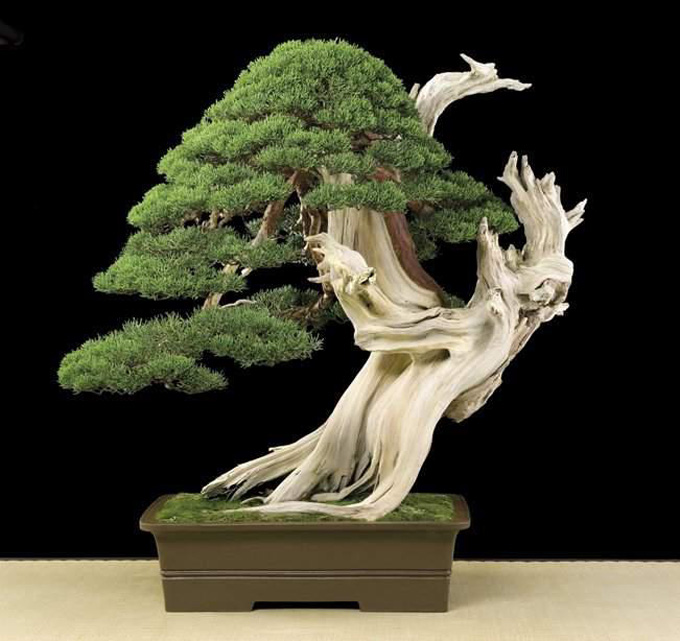

A European bonsai with a Japanese touch. This massive juniper with its wildly sculpted deadwood is reminiscent of bonsai you’d see in Japan in the 80s and 90s. Right down to the quality Japanese pot (unless it’s a Chinese knockoff). The artist is Carlos van der Vaart.

A European bonsai with a Japanese touch. This massive juniper with its wildly sculpted deadwood is reminiscent of bonsai you’d see in Japan in the 80s and 90s. Right down to the quality Japanese pot (unless it’s a Chinese knockoff). The artist is Carlos van der Vaart.

Taking the bonsai scene by storm

There was a time not very long ago when bonsai with a heavy reliance on sculpted deadwood took the bonsai scene by storm. Rather than attempting to ‘make your bonsai look like a tree’ (John Naka’s famous dictum) these more abstract trees were the result of a ‘bonsai as cutting edge art’ attitude: more innovative and less beholden to convention. This approach was pioneered by Masahiko Kimura and was made possible by his introduction of power tools into the world of bonsai.

Rejected, then celebrated

At first Kimura’s Japanese contemporaries rejected his work. Too much too fast. But Kimura’s creative power won out; his bonsai were just too powerful and daring to ignore. Soon his name was known to bonsai enthusiasts around the world. People started experimenting with power tools and suddenly bonsai with wildly sculpted deadwood was showing up everywhere (continued after photo).

At the risk of overstatement: I’m absolutely floored at the over-the-top insanity of this wild and wonderful, slightly tortured, but stunning bonsai. Where on earth did Carlos van der Vaart find deadwood like this?

At the risk of overstatement: I’m absolutely floored at the over-the-top insanity of this wild and wonderful, slightly tortured, but stunning bonsai. Where on earth did Carlos van der Vaart find deadwood like this?

The backlash

Inevitably, some people grew tired the Kimura clones. Grumblings were heard that expressed a distaste for such unnatural looking bonsai (in the eyes of some) and a longing for a more naturalistic aesthetic surfaced. Some people even found it necessary to take sides; naturalistic versus abstract or sculptural, as though they somehow couldn’t coexist.

Peace in our time

Now the controversy seems to have died down. The more natural look is back in vogue, but it’s a natural look that has absorbed the sculptural touch. Carved deadwood abounds, but, in most cases, the desired result is deadwood that looks naturally aged, rather than the highly abstract deadwood that was once so popular. Still, that wildly abstract look pops up now and then. Take Carlos van der Vaart’s trees in this post, for example.

An overly simplified view

Of course, the views expressed in this post are overly simplified. It’s the nature of the beast. If you tried to write a more detailed and well researched history online, no one would take the time to read it. In fact, you can’t really expect anyone to read something the length of this post (if you got this far, you may be the only one).

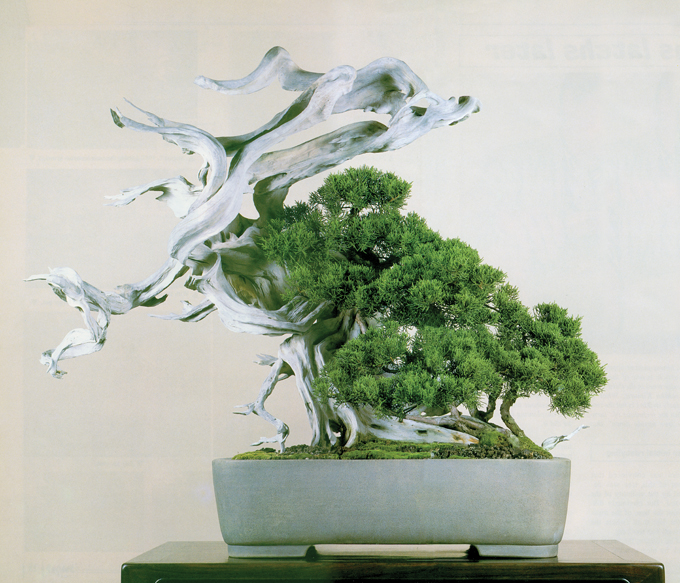

This Shimpaku juniper is one of Masahiko Kimura’s signature bonsai. The foliage looks natural enough, but when it comes to the deadwood, it’s more about a wild flight of creative fancy than about replicating nature. From the back cover of The Magician (and other places).

This Shimpaku juniper is one of Masahiko Kimura’s signature bonsai. The foliage looks natural enough, but when it comes to the deadwood, it’s more about a wild flight of creative fancy than about replicating nature. From the back cover of The Magician (and other places).

I read all of it! Thanks for all the work you do to maintain this blog. I learn so much each time, and find my aesthetic sensibility expanded over time. A very nice addition to the world of bonsai.

Thanks again,

Rick Midthun, a bonsai novice in California (and a customer also).

The main problem I have with these is the conditions required to maintain the deadwood (low humidity, even temperature, covered to keep the dust off, etc.) are at odds with conditions required to keep the tree healthy. When I look at these I feel sorry for the poor tree having to live with a piece of dead wood that is getting more attention than it is. Good bonsai is about the tree, not what it shares it’s pot with.

Dale

Wayne,

Didn’t Dan Robinson take a chainsaw to a bonsai before Kimura ever even dreamed of such an idea? Bristle Cone Pines in California have sported the deadwood attributed to Kimura for centuries. Is Kimura really that “innovative.”? Mother nature cannot be equalled. Why is it that anything with a triangle is supposed to be representative of trees in nature anyway. We need something new. Right now I think Dan Robinson, Nick Lenz, Walter Pall and Robert Steven are the ones people should be emulating. IMHO.

Hi Dale,

Thanks for your comments, though I must take issue.

Many of the trees that have heavy deadwood are dry climate trees that live in places with wide temperature swings and some dust, so keeping them healthy and preserving the deadwood shouldn’t be that difficult.

If you ever get a chance you might want to visit the Bristecone pines in California’s White Mountains (there are other place too). The older ones almost all show massive amounts of deadwood, often with minimal amounts of foliage. Here’s a link: https://bonsaibark.com/2011/01/25/dead-for-one-thousand-years/

Hi Owen,

Thanks for your thoughtful comments (as always).

I don’t know when Kimura first dreamed of taking a chainsaw (or any other power tool to a bonsai) nor do I know when he first did it, though I believe it was some time in the 80s (maybe someone can shed some light on this). I think Dan Robinson first did it publicly in 1980, so it is certainly possible that Kimura got the idea from Dan.

However, doubting Kimura’s innovation seems a little questionable. All you need to do is look at the books The Bonsai Art of Kimura (out of print) or The Magician (available at Stone Lantern) or any number of back issues of Bonsai Today to see how amazingly innovative and skilled Mr Kimura was and is. To me, this is beyond question.

Though I’m not saying you are doing this, but I’ve noticed a tendency in many Westerners to downplay the influence of the Japanese on bonsai (past and present). In my opinion this view is often based on a blend of chauvinism and ignorance. Not to say that there aren’t many extremely gifted Western and other non-Japanese bonsai artists and that the West isn’t catching up to Japan (and to Asia), but that there is no need to try to diminish the influence of the Japanese on the art of bonsai. If you want more informed opinions than mine, talk with people who have apprenticed in Japan, like Michael Hagedorn or Ryan Neil, or to Peter Tea who is currently there. My guess is that they’ll tell you that the level of subtlety and the scope of knowledge of the Japanese masters is still unrivaled in the West.

Wayne,

Touché – chauvinism and ignorance – really? I have numerous books with Kimura’s works (many I purchased from Stone Lantern). The Bonsai in the bottom photo is the one he turned upside down and saved its life. I do not doubt Kimura’s mastery or extensive horticultural skills. My point was that the triangle thing is like listening to nothing but the Beatles over and over again (there’s lots more music being played out there), to the exclusion of everything else. Dan Robinson’s book inspired me so much I read it and looked at the photos over and over and did not feel fatigued. Besides, did you or did you not refer Dale to the real-life photos of Bristle Cone Pines above (not Kimura’s books). The last tree I purchased this year was a yamadori from NEBG. Interestingly, no one knew what species it was. The reason I purchased it was because it looked like an ancient tree with great potential. At the counter Hitoshi said to me “interesting choice, but you know it’s not the classic Japanese-style tree, you know first branch, second branch…” My response was “that’s why I like it, it’s different.”

Hi. I would like to clarify my earlier comments: I didn’t like Carlos’s – the second image – because it appears to me to be a tree trained on dead wood of another species. The dead wood is interesting enough on it’s own without forcing a tree to live with it. I am familiar with Bristlecone pine (Pinus longaeva) by the way: I have a grouping of them that I started from seed growing in the ground on an exposed site in our wet Pacific Northwest climate. They are growing normally, and not showing any dead wood, but they do have a sturdy, tough look about them. I’m going to try air layering some branches off to establish in pots to see if I can grow a presentable Bristlecone pine bonsai without dead wood!

Dale

Thanks again Owen,

Points well taken. I like your Beatles analogy.

I don’t think I accused you of chauvinism or ignorance, though I did use your comment as a platform for expressing that view, perhaps unskillfully. Mea culpa.

Maybe it’s what I perceive as the more egoless approach of many of the Japanese bonsai artists that I really like. Trying to sort through and make sense of bad Bonsai Today translations (from Japanese to Spanish to English) one thing that kept coming through, was a certain humbleness and view of life that went beyond just good bonsai and not so good bonsai. A view where bonsai and art become vehicles for experiencing feeling (that word came through a lot) and sensitivity. I think this view leads to a commitment to patience and an attention to detail that is still largely missing in Western bonsai.

This is not to say that Western bonsai is inferior; passion, artistry and fearlessness are certainly present in the bonsai of the best of the West, but when it comes to attention to detail and refinement that is the result of deep discipline, we still have much to learn from our Japanese bonsai friends.

Thanks Dale,

Good comments.

We have the same experience here in the wet Northeast; Bristlecones grow and take on a tough aged look, with dark heavy bark. No deadwood (not enough time anyway) and a look that is quite different that what you see in California’s White Mountains.

Sadly, I killed a 25 year old Bristlecone last year when I tried to create too much deadwood too fast (it’s not the first tree I’ve killed, but it still haunts me a bit). I guess my advice would be to take your time with yours.

Good luck!

Wayne,

“This is not to say that Western bonsai is inferior; passion, artistry and fearlessness are certainly present in the bonsai of the best of the West, but when it comes to attention to detail and refinement that is the result of deep discipline, we still have much to learn from our Japanese bonsai friends.”

I agree with this totally! But, sadly, I think this is a cultural difference that some Westerners are reluctant to admit or accept. I have an Eastern Larch in the ground for about 5 years now that I’m trying to enhance the nebari via the tourniquet technique (I’m addressing really bad inverse taper at the base). After reading Nick Lenz’s work on how he deals with this I was dismayed to learn that he recommends ten years of in-ground growing to correct this. I have 5 more years to go! In this vein, when you consider that Saburo Kato waited until the ninth decade of his life before he thought his work was worth exhibiting it boggles my American mind.

Owen,

Yeah. The long view seems more Asian than Western, where instant gratification seems to be the norm. But then, the ground is always shifting so maybe these types of generalizations won’t hold up. I think more of us are coming around to Nick’s 10 year view. That’s a good start.