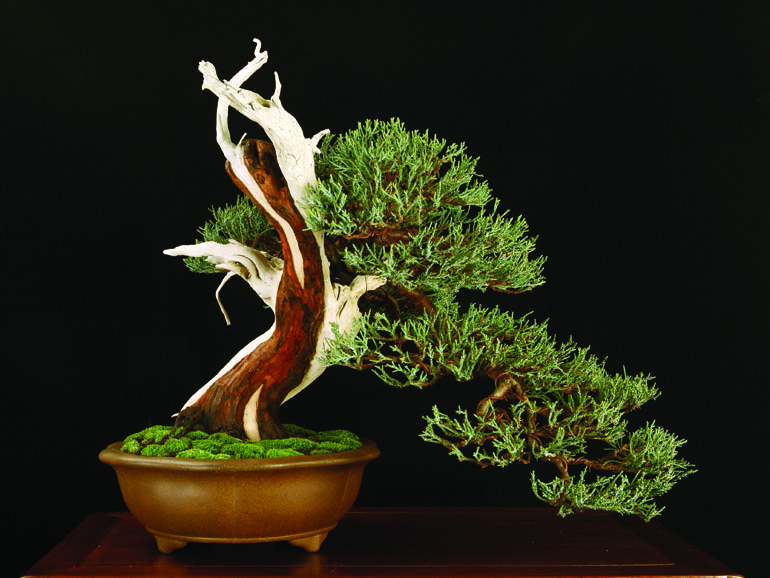

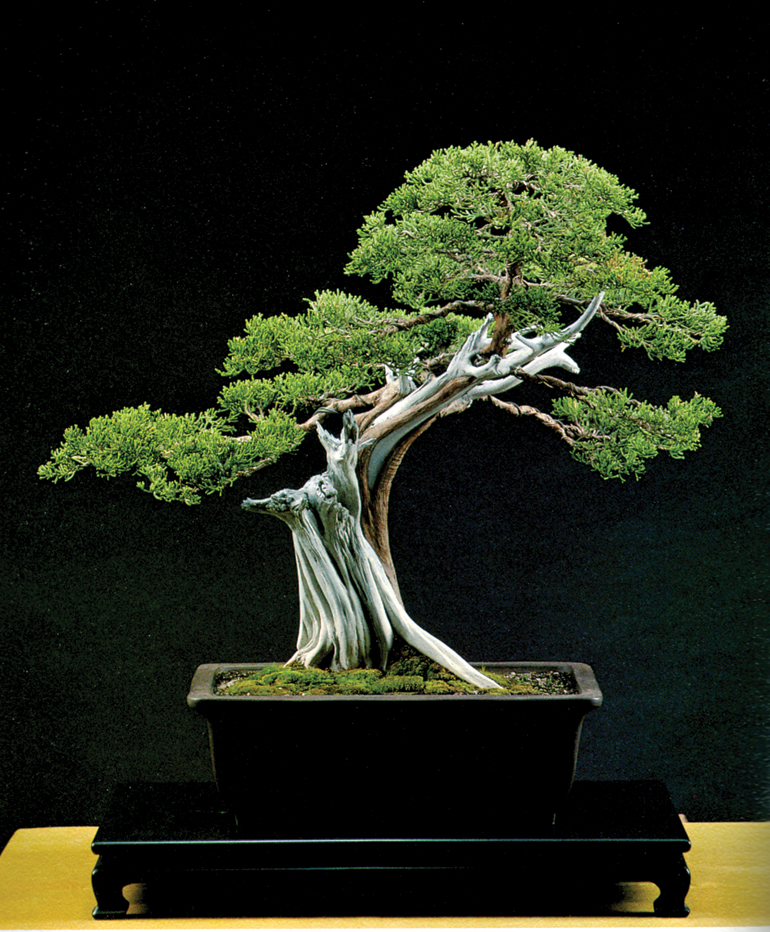

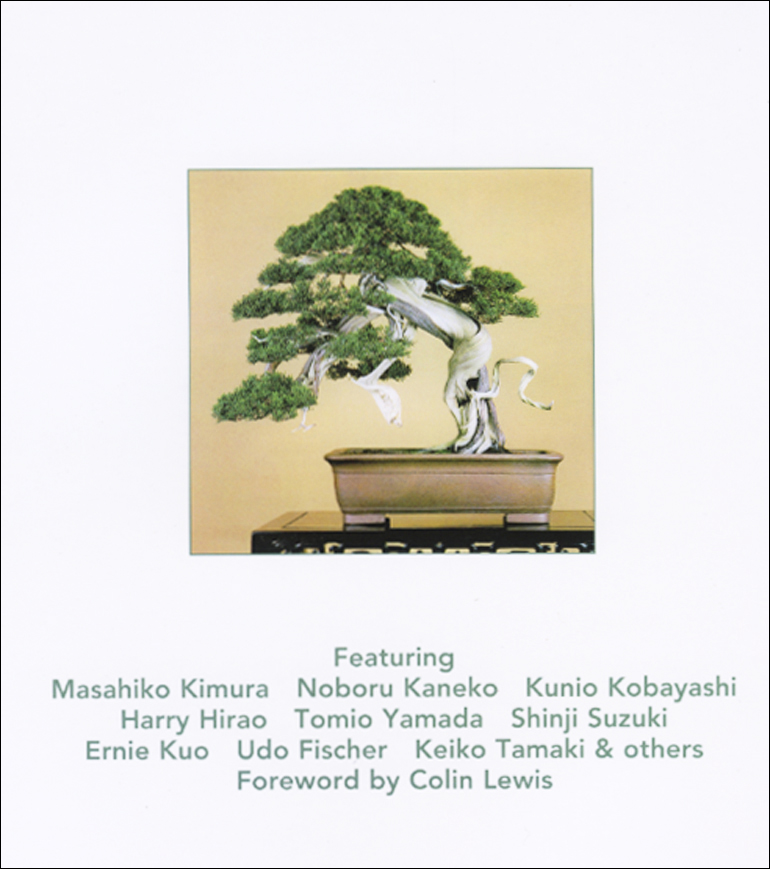

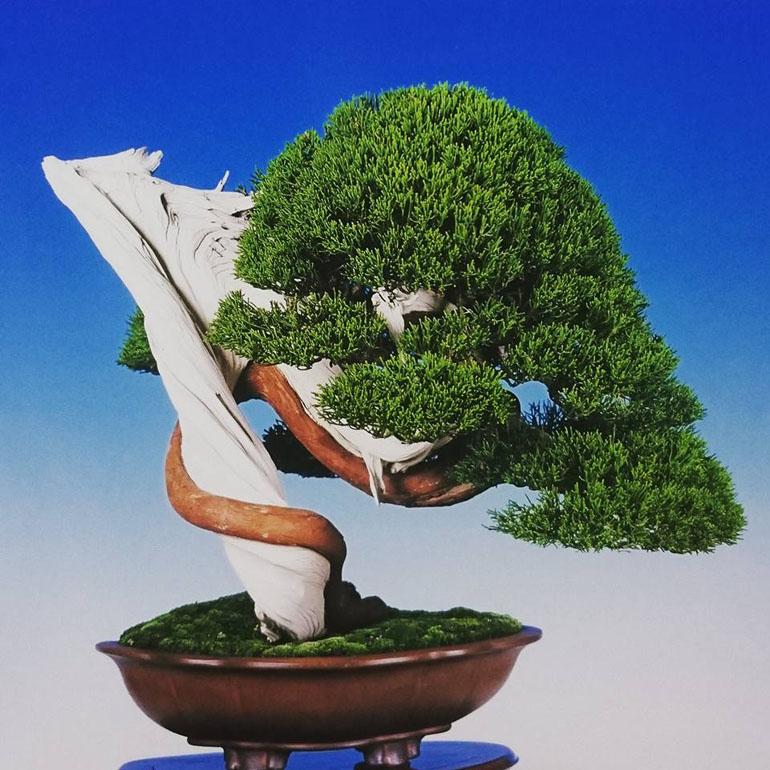

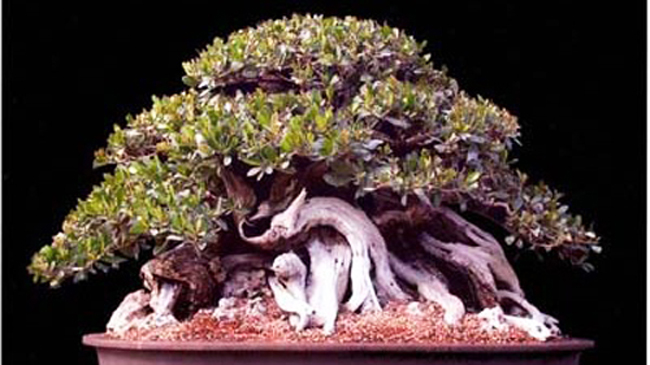

Rocky Mountain Juniper (Juniperus scopulorum) collected by Andrew (aka Andy) Smith and first styled by Walter Pall. It would hard to find a better pair for the job. Andy (Golden Arrow Bonsai) is a professional forester, master collector of wild bonsai and a bonsai artist in his own right, and Walter Pall is a world famous bonsai artist, teacher, trouble maker (in the positive sense of course) and owner of a very impressive bonsai collection. The photograph is by Walter. My apologies for the fuzz. It's the result of dramatically increasing the image size. On balance I think this size presents a better look at the tree in spite of the fuzz.

Rocky Mountain Juniper (Juniperus scopulorum) collected by Andrew (aka Andy) Smith and first styled by Walter Pall. It would hard to find a better pair for the job. Andy (Golden Arrow Bonsai) is a professional forester, master collector of wild bonsai and a bonsai artist in his own right, and Walter Pall is a world famous bonsai artist, teacher, trouble maker (in the positive sense of course) and owner of a very impressive bonsai collection. The photograph is by Walter. My apologies for the fuzz. It's the result of dramatically increasing the image size. On balance I think this size presents a better look at the tree in spite of the fuzz.

Still on vacation and enjoying the wonders of the West Coast. Soon we’ll be home and ready to put together some new posts for you. Meanwhile, we’re taking the easy way out. This one originally appeared April, 2014.

This morning I was looking for photos of Lodgepole pine bonsai when I stumbled upon an old interview with Andy Smith that appeared on The Art of Bonsai Project blog, way back in 2005. It’s a great interview. So great that we’re going to post the whole thing and encourage you to jump in and enjoy Andy’s unique insights into wild bonsai, the art of collecting and much more.

The Art of Bonsai Project Interview with Andrew Smith

Andrew Smith is a contract forester in South Dakota’s Black Hills. He became fascinated with bonsai in 1994 while collecting core specimens from very ancient pines to use in past climate studies.

Smith transplants 300-400 trees per year for bonsai and has supplied demo and workshop trees to many of the world’s best bonsai artists. He enjoys learning about this beautiful and extraordinary art and meeting with other enthusiasts around the country.

The following is an on-line interview conducted with Andy Smith (continued after the photo):

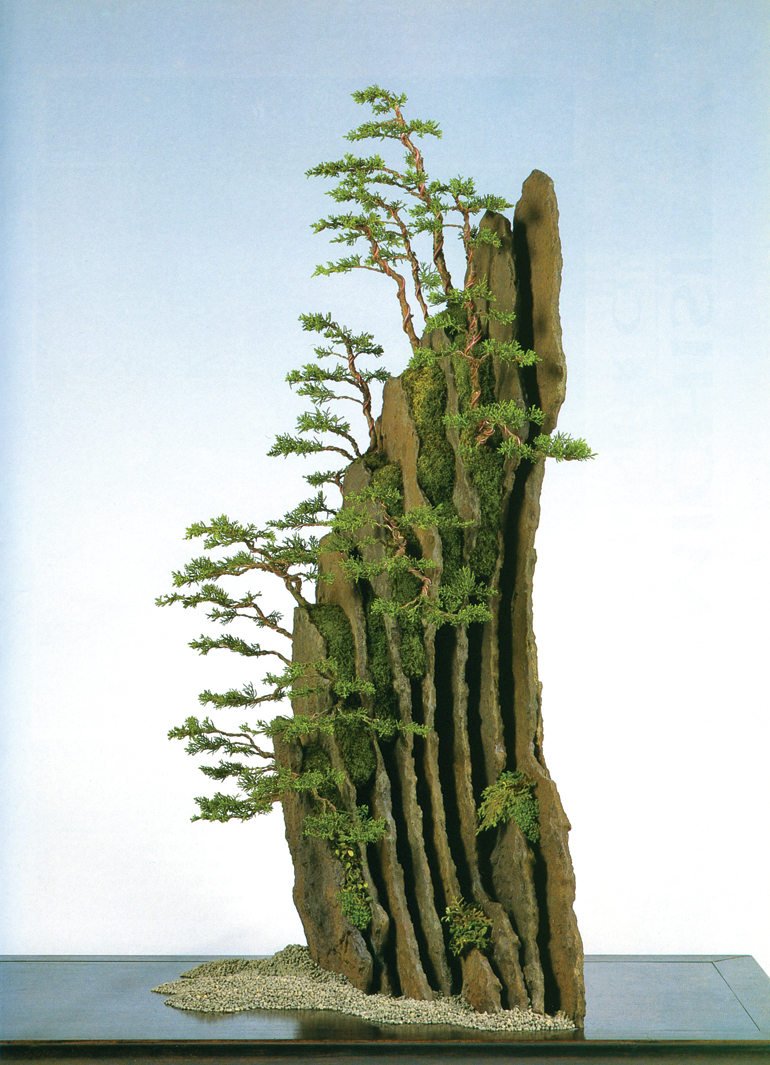

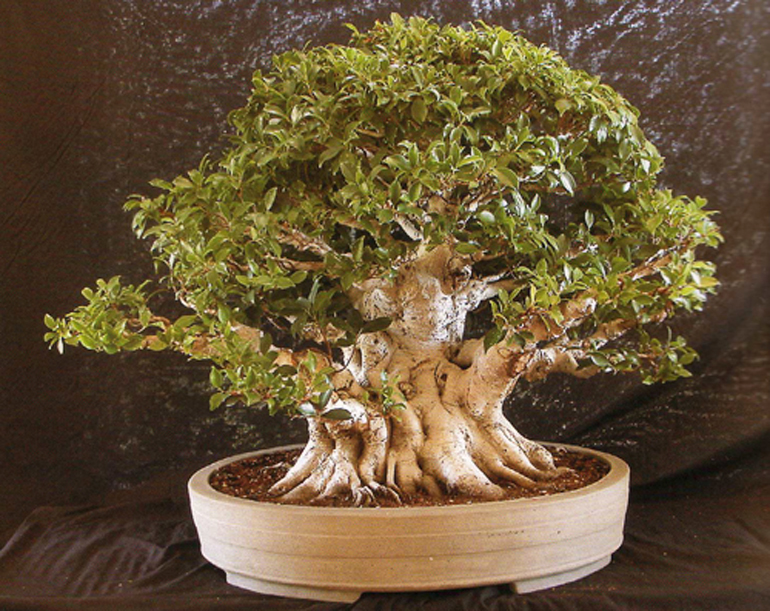

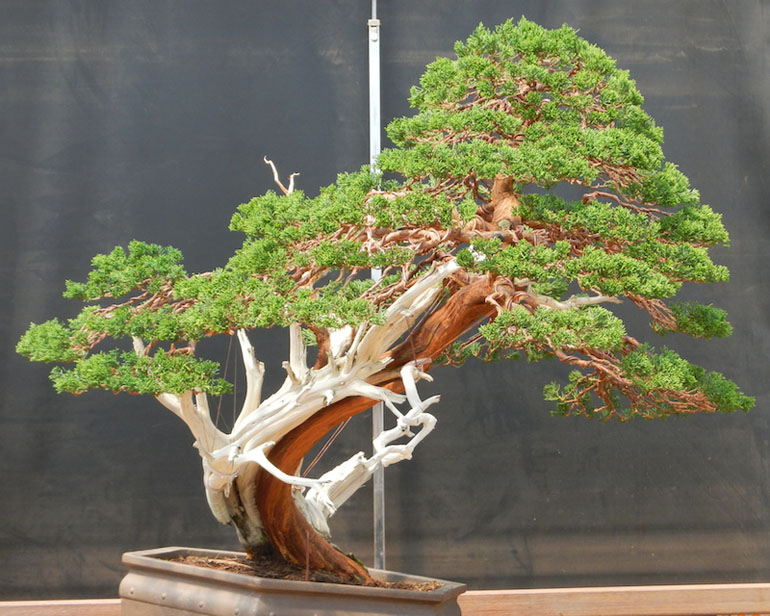

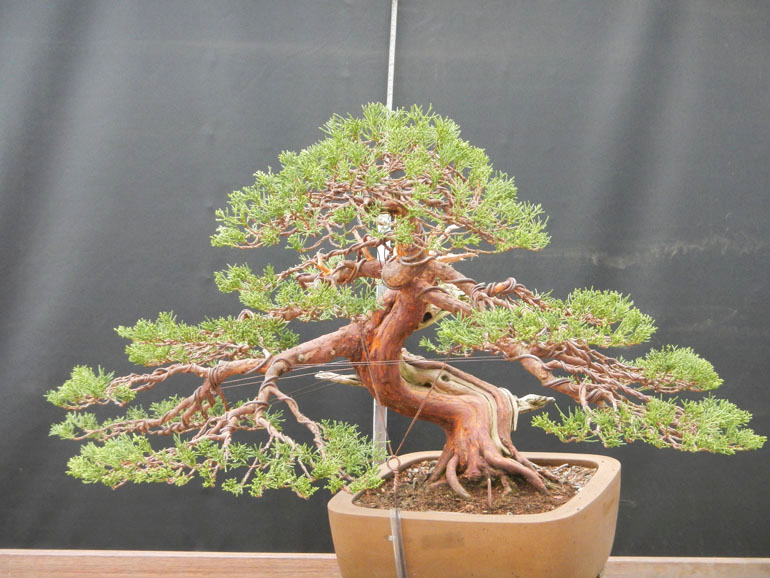

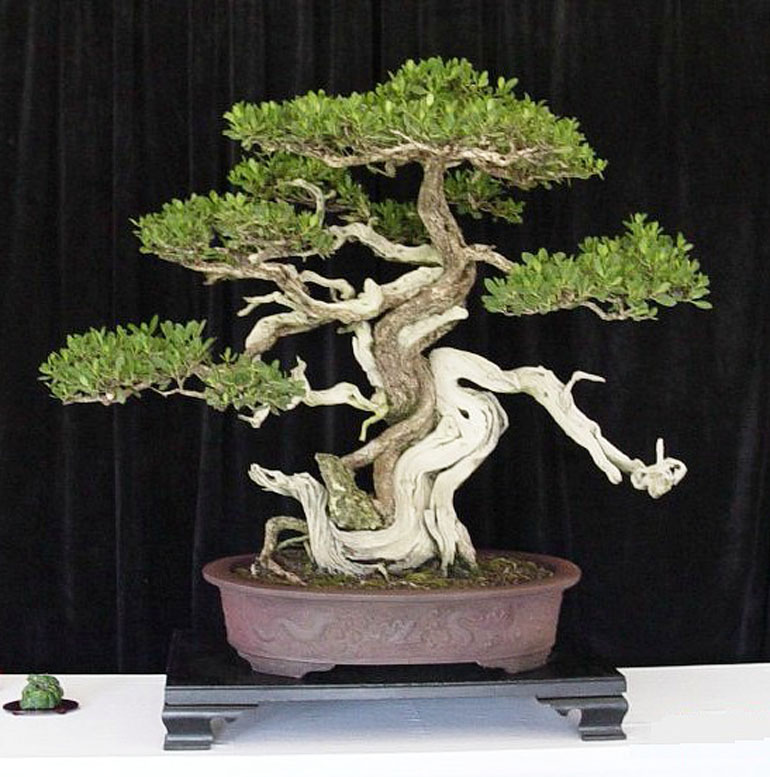

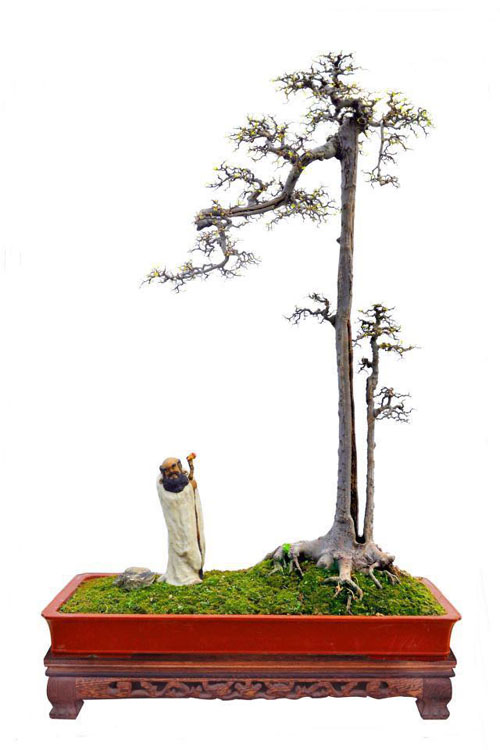

Another Rocky Mountain Juniper that was collected by Andy Smith and first styled by Walter Pall. Photograph by Walter.

Another Rocky Mountain Juniper that was collected by Andy Smith and first styled by Walter Pall. Photograph by Walter.

AoB: Andy, how do you answer the critics who insist that removing trees from a supposedly pristine environment is detrimental to that environment.

Andy: That depends upon your values and goals for the particular environment in question. For instance, most of my trees come from public lands and the permit process (in my opinion) is well regulated. I pay between $5 and $10 per tree for the right to collect in certain areas (no refunds if they die!). But there are huge areas that are off limits to collecting; for instance all wilderness areas; areas with high recreational value such as along hiking trails and near campgrounds and lakes; wildlife preserves; national monuments; state and national parks; along heavily travelled roads; areas with spiritual, historical or special visual significance; etc.

In these areas the guiding management principles place a higher value on the aesthetic, spiritual and natural qualities of the environment than they do on someone, like me, being able to go out and pursue an interest that might change the landscape somewhat.

The areas that are open to collecting are usually the same areas that are open to other resource extraction. In other words these areas might well be logged, grazed or mined at some point in time, or at least such uses are not prohibited.

Andy beside the large pine that he collected in his How to collect Wild Trees DVD.

Andy beside the large pine that he collected in his How to collect Wild Trees DVD.

Another thing to consider is the scale of the enterprise. I collect about 300-400 trees, from several different National Forests, every year, which is far more than anyone else I know. And it takes a huge amount of time, effort and energy to do that.

Meanwhile, the Forest Service is trying to control burn about 8,000 acres a year just here in the Black Hills alone, and many, many thousands more nationwide. This is done to reduce fuel loading and prevent catastrophic wildfires. I understand that it needs to be done but they kill more potential bonsai doing that in one year than I will collect in ten lifetimes. Consider that we recently had a wildfire here that burned over 130 square miles. The fire damage is worse than an atomic bomb would cause. It’s amazing, that in many places you can look from horizon to horizon and not see one live tree.

Continue reading What You Do to the Land You Do to Yourself

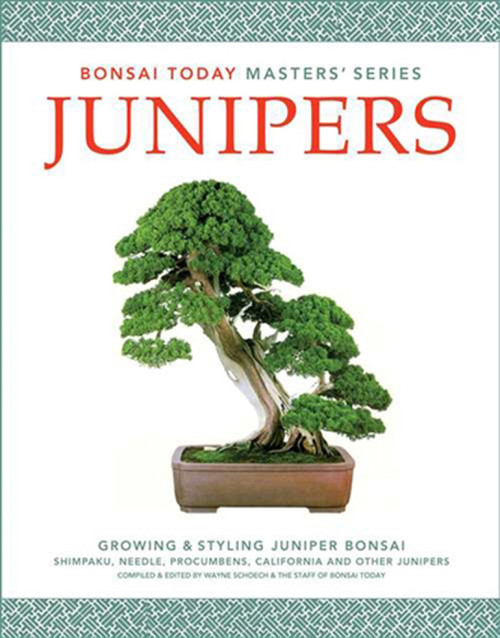

This Sierra juniper by Boon Manakitivipart is one of three trees by Boon that appears in the gallery section of our newly reprinted Juniper Masters' Series book.

Do you recognize this face?

Do you recognize this face?

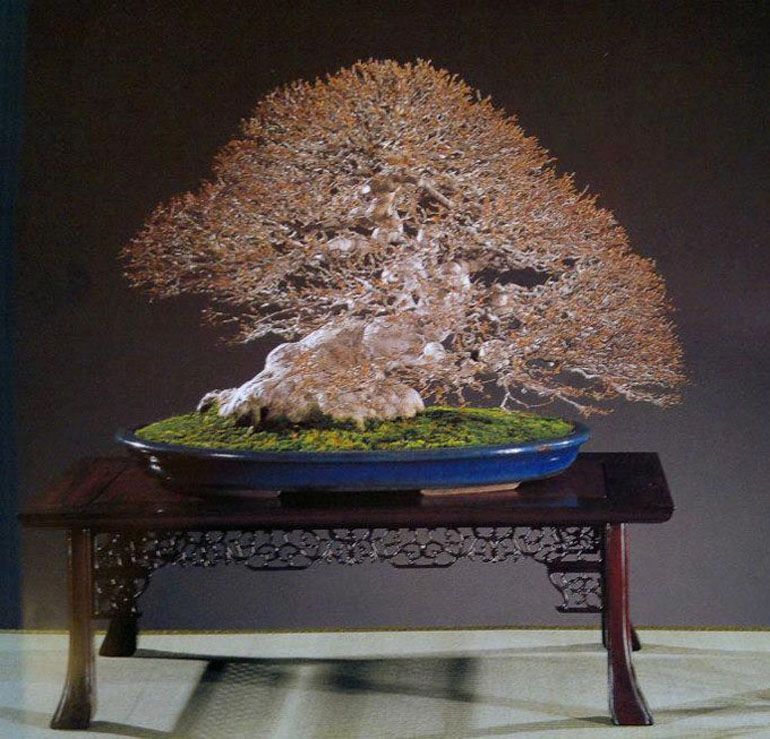

Buttonwood by Ed Trout. The photo is from

Buttonwood by Ed Trout. The photo is from  I found this monster by Jim Smith in the

I found this monster by Jim Smith in the

Avant-garde bonsai. This fluid tree with its distinctive flying pot is from Bonsai Do. The caption says with Tony Tickle (I visited

Avant-garde bonsai. This fluid tree with its distinctive flying pot is from Bonsai Do. The caption says with Tony Tickle (I visited  Spectacular, if just a little fuzzy. The caption says with

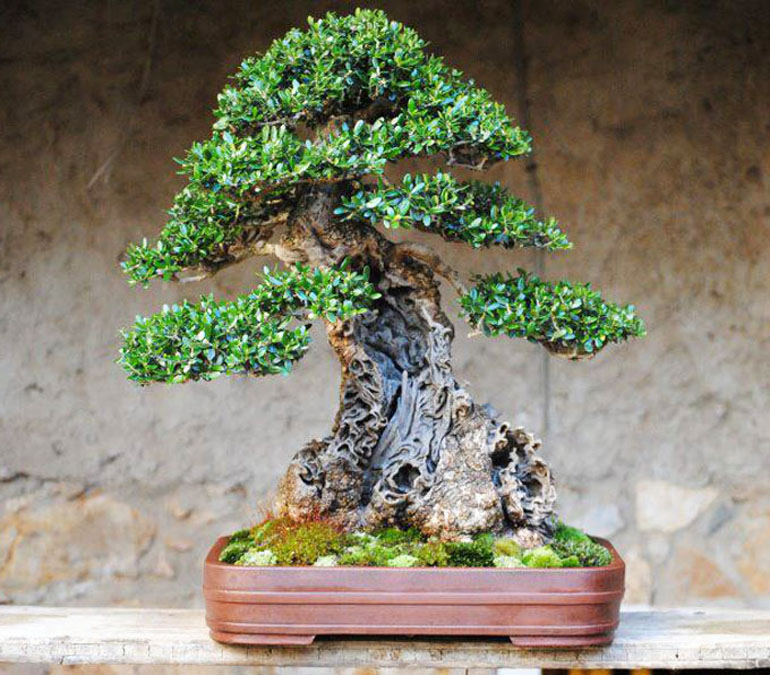

Spectacular, if just a little fuzzy. The caption says with  I'm not sure I've ever seen deadwood patterns quite like this. It's a European olive and it belongs to

I'm not sure I've ever seen deadwood patterns quite like this. It's a European olive and it belongs to

Rocky Mountain Juniper (Juniperus scopulorum) collected by Andrew (aka Andy) Smith and first styled by Walter Pall. It would hard to find a better pair for the job. Andy (

Rocky Mountain Juniper (Juniperus scopulorum) collected by Andrew (aka Andy) Smith and first styled by Walter Pall. It would hard to find a better pair for the job. Andy ( Another Rocky Mountain Juniper that was collected by Andy Smith and first styled by Walter Pall. Photograph by Walter.

Another Rocky Mountain Juniper that was collected by Andy Smith and first styled by Walter Pall. Photograph by Walter.