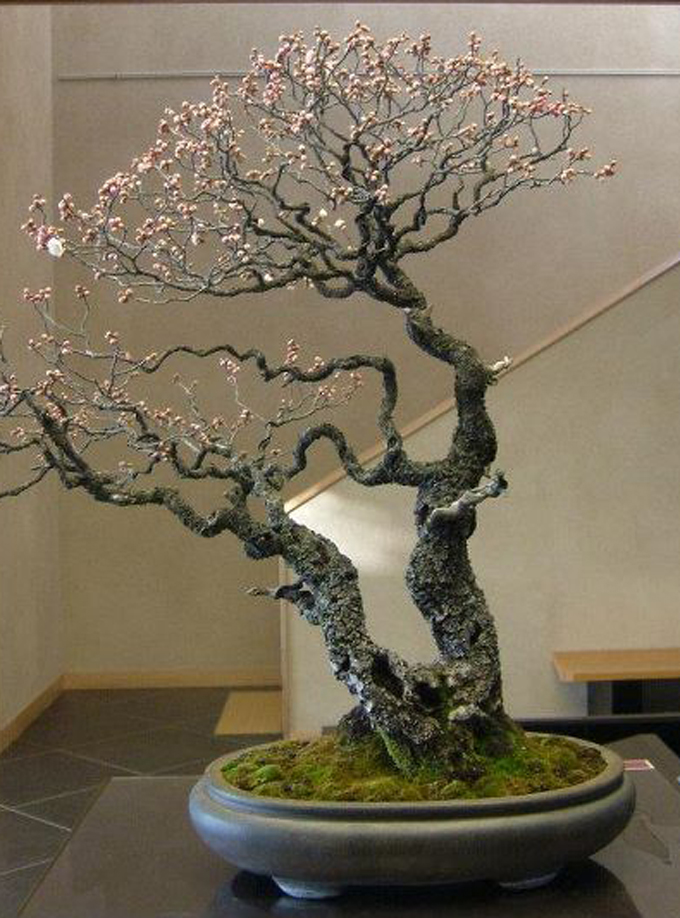

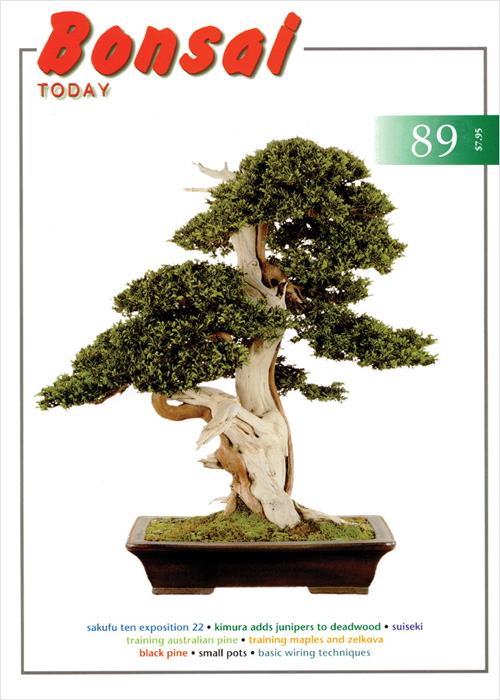

Like most bonsai, this one has been wired. In fact, there’s visible wire on it right now. It’s a Shimpaku that’s from a chapter in our Masters’ Series Juniper book, titled Keiko Tamaki’s Deft Touch.

Like most bonsai, this one has been wired. In fact, there’s visible wire on it right now. It’s a Shimpaku that’s from a chapter in our Masters’ Series Juniper book, titled Keiko Tamaki’s Deft Touch.

It’s time to reach back into our archives once again (from May, 2013). This time our motives are almost purely commercial. We’ve just put up a big Bonsai Wire Sale (20% to 30% off all wire) and that’s something you should know about. BTW: I think this post is worth re-posting even without our commercial motives; you might find the information useful, and I’m sure you’ll like the photos.

Most bonsai are wired at some stage in their development. In fact, bonsai that have been around for a long time may have been wired repeatedly over the years. There are very good reasons for this, not the least of which is, it is often very difficult to get decent results without wire. There’s much more that be can said about this but we’ll leave that for another time.

Anodized aluminum wire is by far the most popular type of wire for bonsai, at least here in the Western world (the other choice is copper wire). We sell both Japanese (Yoshiaki brand) and Chinese (Bonsai Aesthetics brand) anodized aluminum wire and, as a result, we get plenty of question about the difference.

Put simply here’s the difference: Yoshiaki wire is a little stiffer than Bonsai Aesthetics wire. Stiffer means slightly more difficult to use, but a little better holding power.

However, holding power versus ease of use is not the whole story. There are at least two other things to consider: the price and the type of tree you are working on.

When it comes to price, Bonsai Aesthetics wire is hard to beat. It’s such a good deal that even though you have to use slightly heavier wire to get the same holding power, you still save a considerable amount of money.

Types of trees can be broken down into four very general categories: conifers, deciduous trees, temperate zone broad leaf evergreens and tropicals. We’ll just skim the surface here and maybe dig a little deeper in future post.

Most conifers require stiffer wire than other trees, so copper works quite well (it’s strongest of all and very good for heavy branches). However, many people eschew copper wire for the ease and lower cost of aluminum. If you do use aluminum you’ll need a gauge that is quite a bit thicker than the gauge for copper.

Deciduous trees are usually wired with aluminum as are most temperate zone broad leaf evergreens trees. Either Yoshi or Bonsai Aesthetics will work depending on the size of the branch and your preference.

Many types of tropicals are seldom wired, if at all. If you do have a tropical that you’d like to wire, we recommend Bonsai Aesthetics aluminum wire. This is in part because tropicals grow so fast (especially when they’re in the tropics) that you’ll be taking it off not long after you put it on, so why spend the extra money?

At this point, I’d be well-served to borrow Michael Hagedorn’s disclaimer: “There are plenty of exceptions to everything I just said, which naturally makes blogging about bonsai a total disaster.”

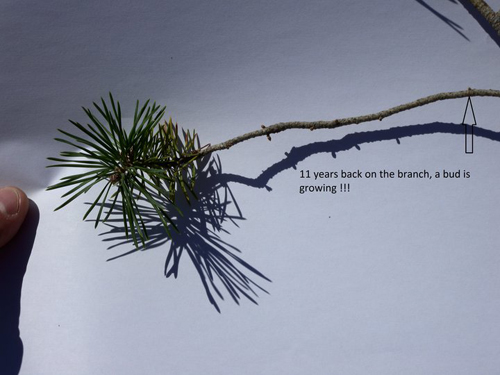

One good reason the best Japanese bonsai look more refined than most Western bonsai is because Japanese bonsai artists wire all the way out to the tips of the smallest twigs.

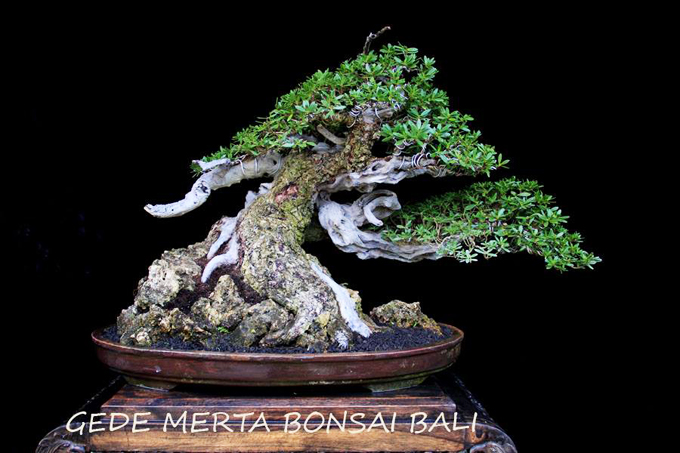

Once the wire is on (copper in this case) it’s time to bend. This photo and all the others in this post are from our Masters Series Juniper book.

Once the wire is on (copper in this case) it’s time to bend. This photo and all the others in this post are from our Masters Series Juniper book.

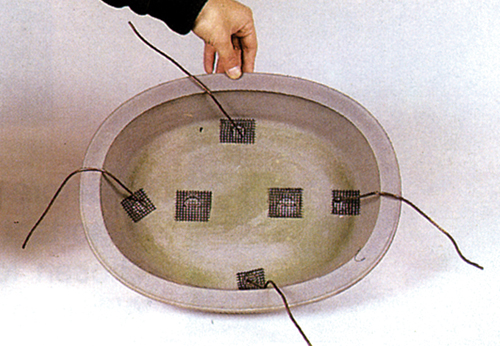

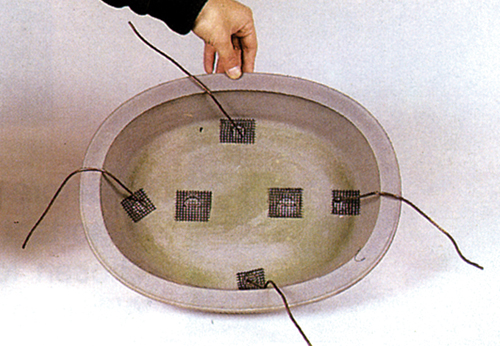

Another good use for wire. If you want to prevent future mishaps, both small and large, it’s an excellent idea to wire your tree into the pot.

Another good use for wire. If you want to prevent future mishaps, both small and large, it’s an excellent idea to wire your tree into the pot.

Spring Bonsai Wire Sale. 20% to 30% off all Bonsai Wire.

Spring Bonsai Wire Sale. 20% to 30% off all Bonsai Wire.

This ancient three-quarters-dead Limber pine (Pinus flexilis) is clinging for its life on Cusick Mountain in the southern part of Eagle Cap Wilderness in northeastern Oregon. I borrowed both photos in this post from Backcountry Bonsai.

This ancient three-quarters-dead Limber pine (Pinus flexilis) is clinging for its life on Cusick Mountain in the southern part of Eagle Cap Wilderness in northeastern Oregon. I borrowed both photos in this post from Backcountry Bonsai. A magnificent monster! At first glance I thought there’s a strange purple flower growing at the tree’s base. Turns out it’s a backpack that serves at least too functions: it provides a sense of scale, and it distracts from the beauty of the tree just a bit. I suppose it goes without saying that the yellow dots are flowers.

A magnificent monster! At first glance I thought there’s a strange purple flower growing at the tree’s base. Turns out it’s a backpack that serves at least too functions: it provides a sense of scale, and it distracts from the beauty of the tree just a bit. I suppose it goes without saying that the yellow dots are flowers.