Lakeside with Lingering Snow, our second in a series of plantings from Toshio Kawamoto’s Saikei classic. The trees are the same (cryptomeria) as in our last post (A Deep Ravine in a Shallow Pot), the pot is almost the same and the landscape is similar, though this one is softer. The focal point, the large single mountain stone that elevates the planting from good to extraordinary is enhanced by a little touch of snow. The author doesn’t say what the snow is and it’s hard to tell from the photo. It would be ideal if it were simply part of the rock.

Lakeside with Lingering Snow, our second in a series of plantings from Toshio Kawamoto’s Saikei classic. The trees are the same (cryptomeria) as in our last post (A Deep Ravine in a Shallow Pot), the pot is almost the same and the landscape is similar, though this one is softer. The focal point, the large single mountain stone that elevates the planting from good to extraordinary is enhanced by a little touch of snow. The author doesn’t say what the snow is and it’s hard to tell from the photo. It would be ideal if it were simply part of the rock.

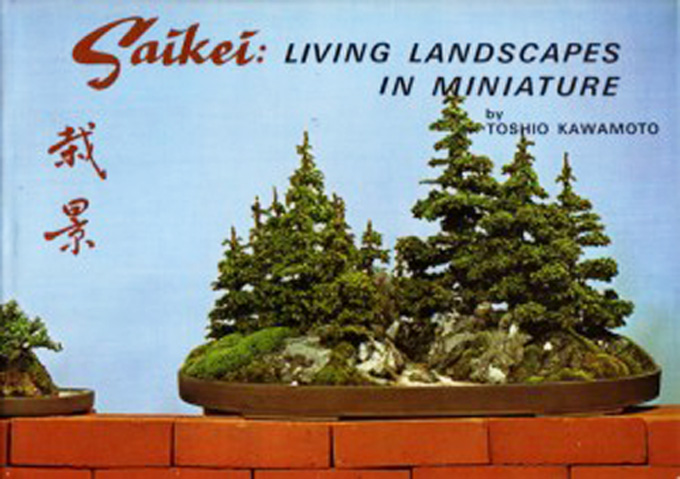

Thought we might as well continue our series on Toshio Kawamoto’s remarkable book, Saikei, Living Landscapes in Miniature. We first ran this series back in January 2010, and now, because I’m still out of town and can’t seem to find time to put together new posts, why not give it another go?

An invitation

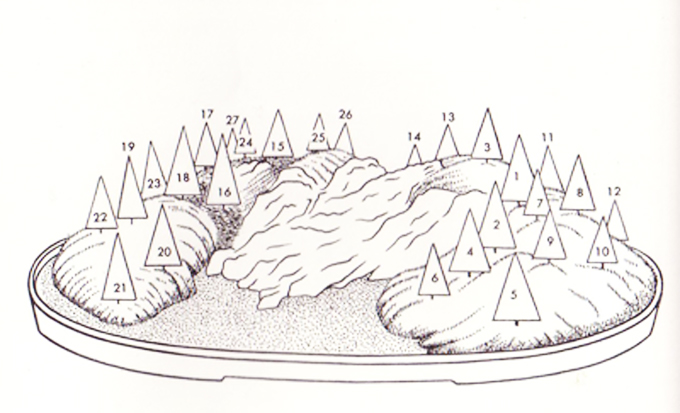

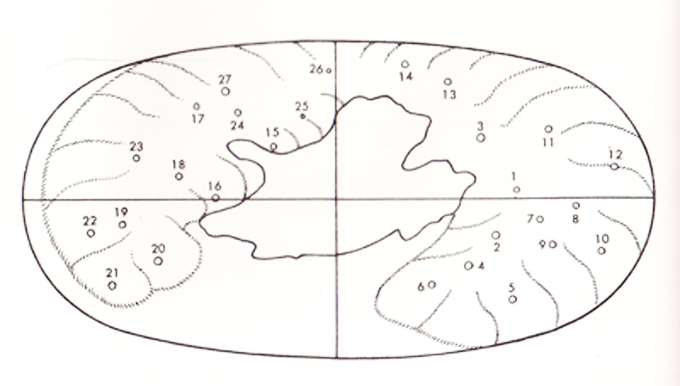

The purpose of this section is to show how to create lakeside saikei. In fact, if you look at the drawings throughout the book it’s almost as if the author is inviting you to duplicate his work. If you don’t have the book, don’t worry, we’ll be posting photos and the drawings. Meanwhile you’ve got two to go on (deep ravine and this one).

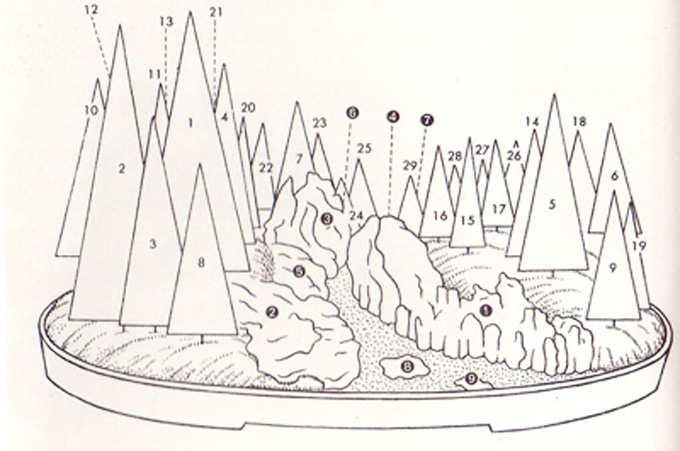

Front schemata. The pot is 26″ x 13″ (66cm x 33cm) unglazed oval by Tokoname. There are 27 cryptomeria that range from 2.5″ to 4.5″ (6cm to 11.5cm) tall. The soil is regular bonsai soil (he doesn’t say which regular bonsai soil, but the Japanese almost always use akadama or an akadama mix for conifers). The other materials are peat (it’s unclear how he uses it, see below), green moss and black river pebbles (the lake).

Front schemata. The pot is 26″ x 13″ (66cm x 33cm) unglazed oval by Tokoname. There are 27 cryptomeria that range from 2.5″ to 4.5″ (6cm to 11.5cm) tall. The soil is regular bonsai soil (he doesn’t say which regular bonsai soil, but the Japanese almost always use akadama or an akadama mix for conifers). The other materials are peat (it’s unclear how he uses it, see below), green moss and black river pebbles (the lake).

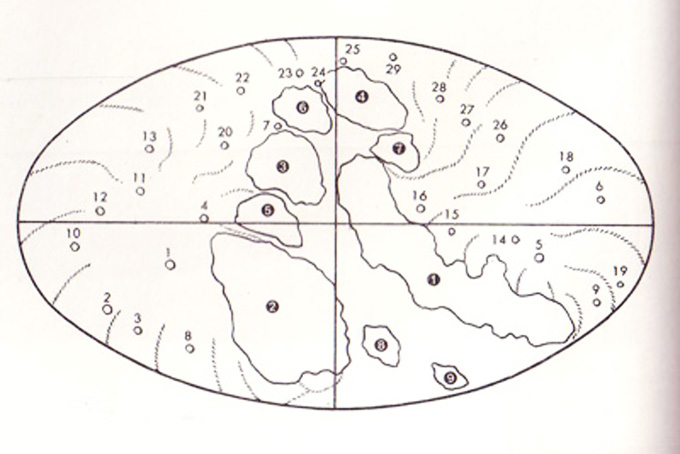

Bird’s eye view. The lake (or piece of it) is off center which helps create a natural, uncontrived feel. The landscape is soft and inviting. This softness is enhanced by the way the hills and the rock flow into each other (the photo and front schemata show this best). The small size of the trees (much smaller than the deep ravine saikei) and the way they sort of sink into the land, further enhances this easy, peaceful, almost feminine feel. Altogether it looks like a place where you might like spend some time. Just relaxing and enjoying the view and feel of the land, and the soft breezes off the lake. You might even go for a swim.

Bird’s eye view. The lake (or piece of it) is off center which helps create a natural, uncontrived feel. The landscape is soft and inviting. This softness is enhanced by the way the hills and the rock flow into each other (the photo and front schemata show this best). The small size of the trees (much smaller than the deep ravine saikei) and the way they sort of sink into the land, further enhances this easy, peaceful, almost feminine feel. Altogether it looks like a place where you might like spend some time. Just relaxing and enjoying the view and feel of the land, and the soft breezes off the lake. You might even go for a swim.

Make my day

If you want to try one and send a photo, it just might make my day. If you don’t want to do that (and most of you won’t), at least you can post a comment. Otherwise, this job can seem a bit like…. (you can insert a good Texas down home expression here that conveys something like shooting in the dark).

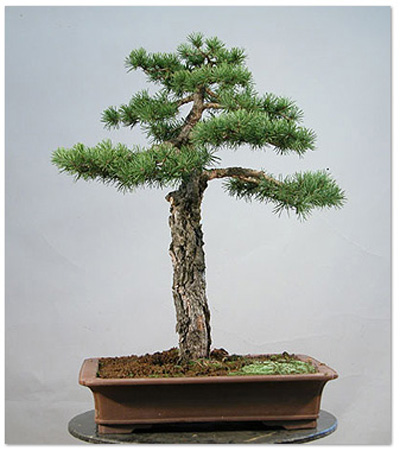

Mike’s original photo that was submitted to Robert.

Mike’s original photo that was submitted to Robert.

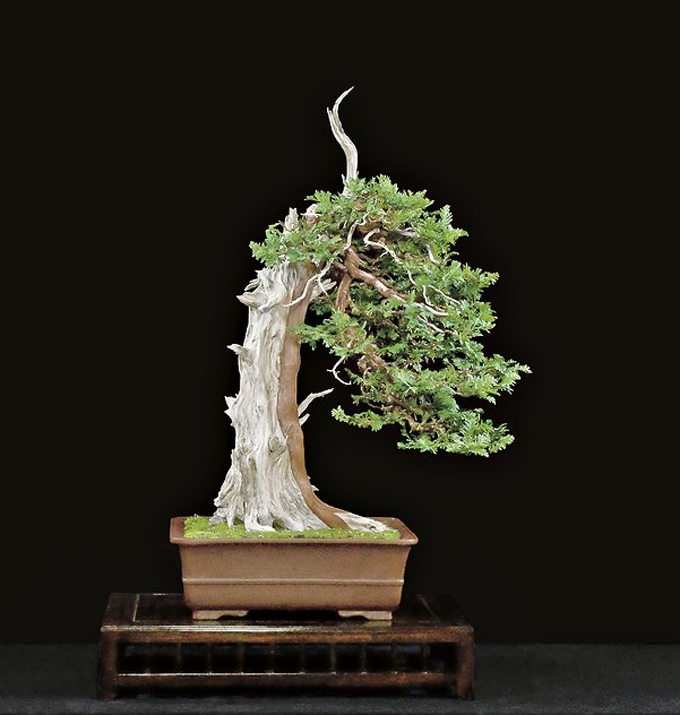

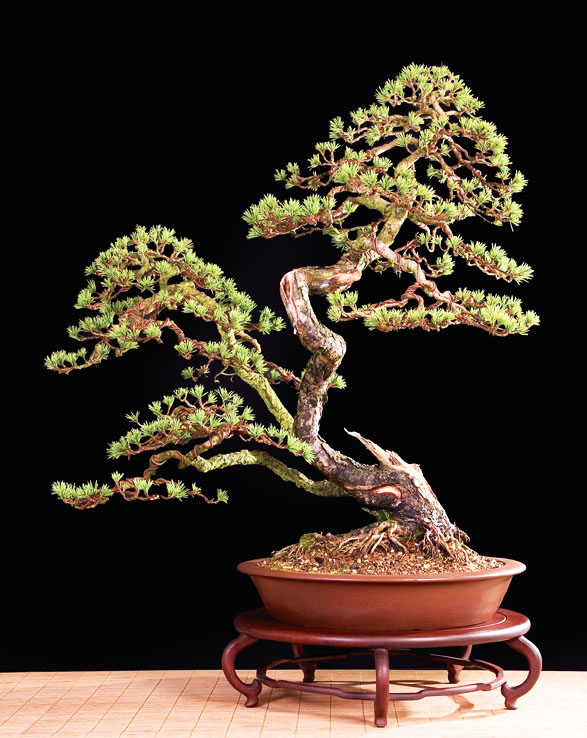

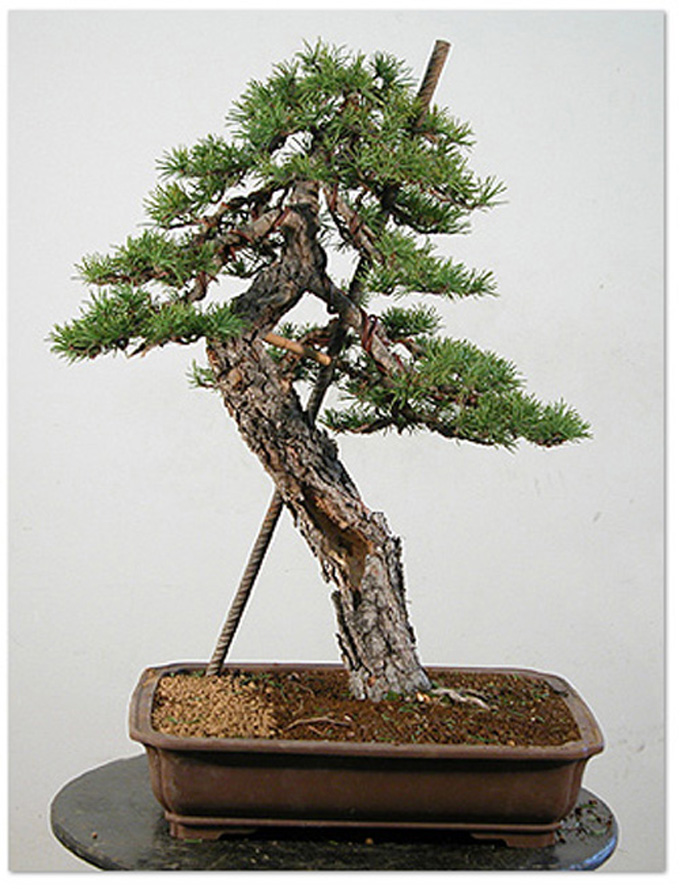

Before. This tree is begging for a good rebar fix.

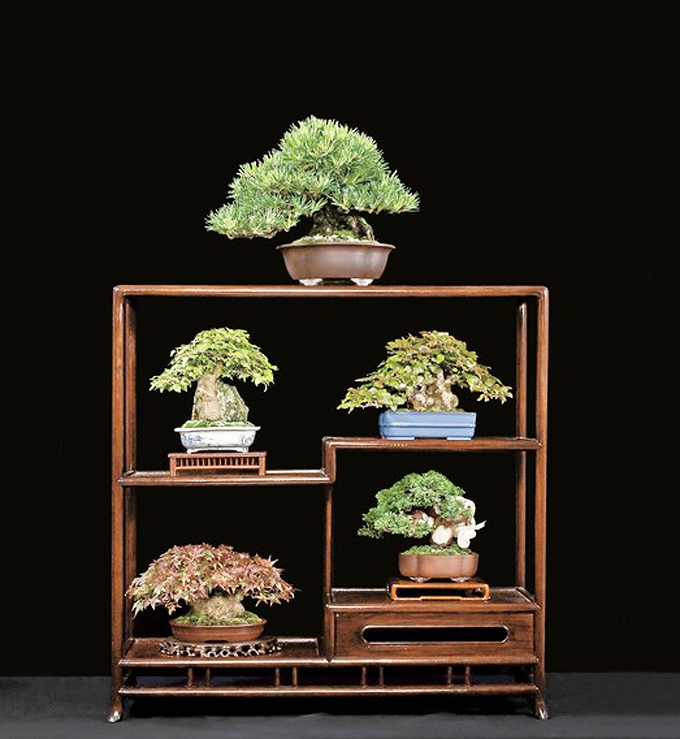

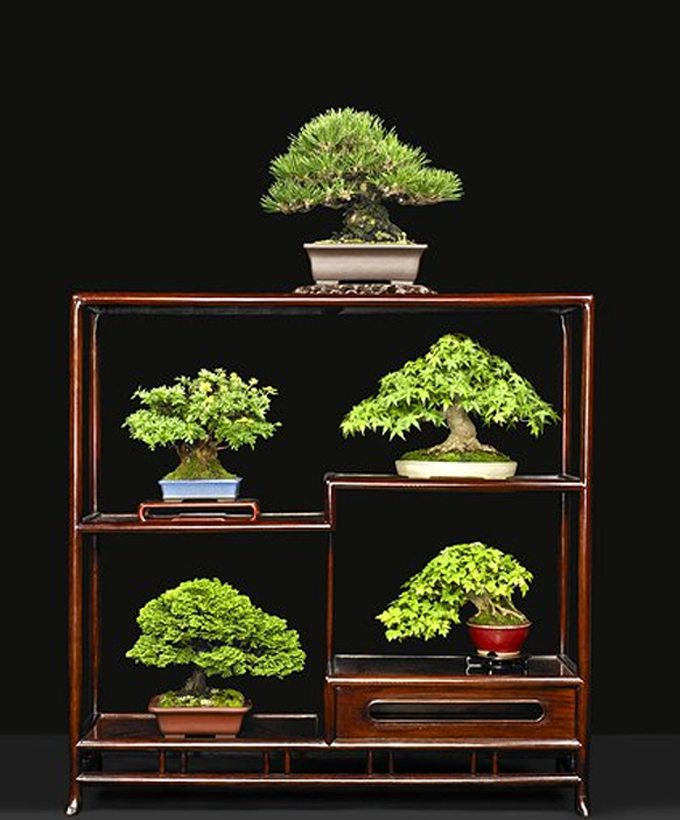

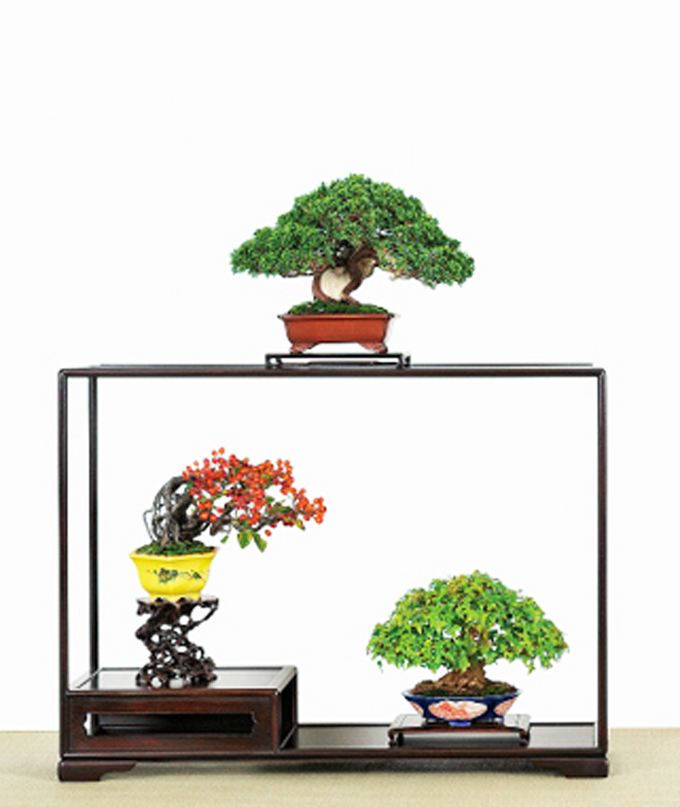

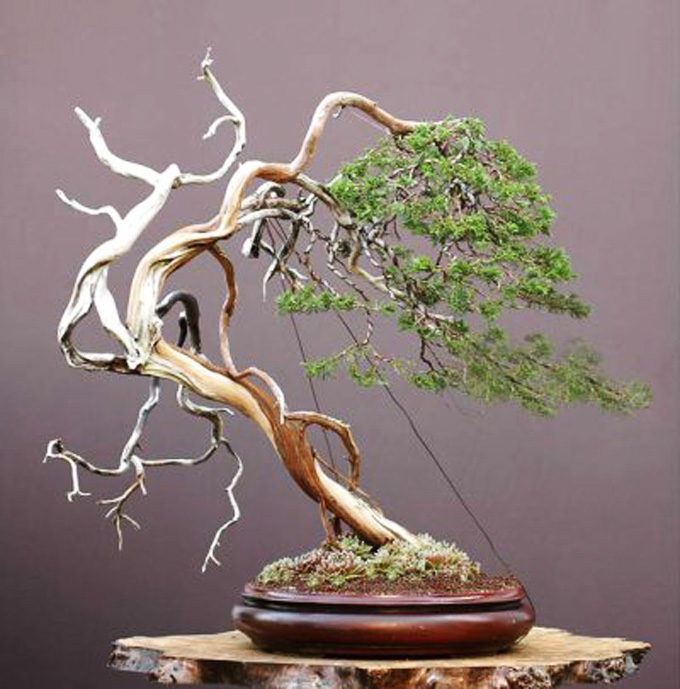

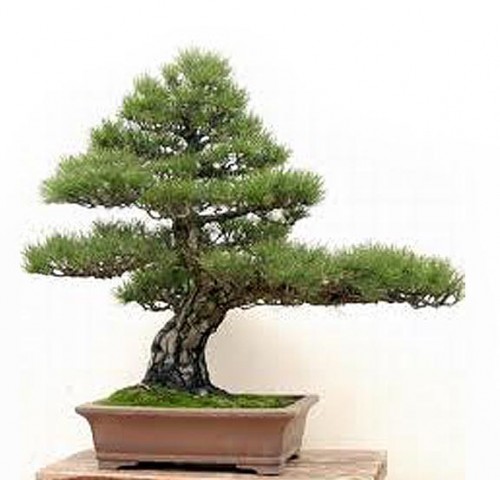

Before. This tree is begging for a good rebar fix. Full cascade Scot’s pine by David Benavente. You can provide the adjectives.

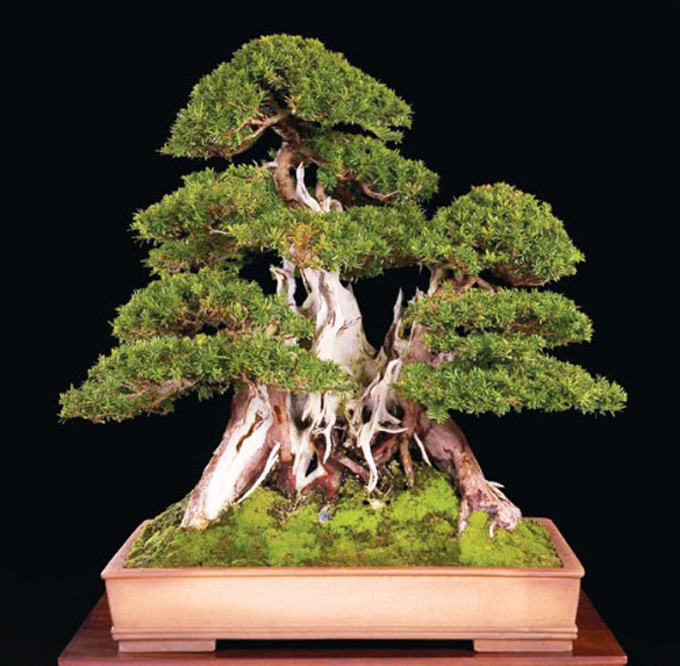

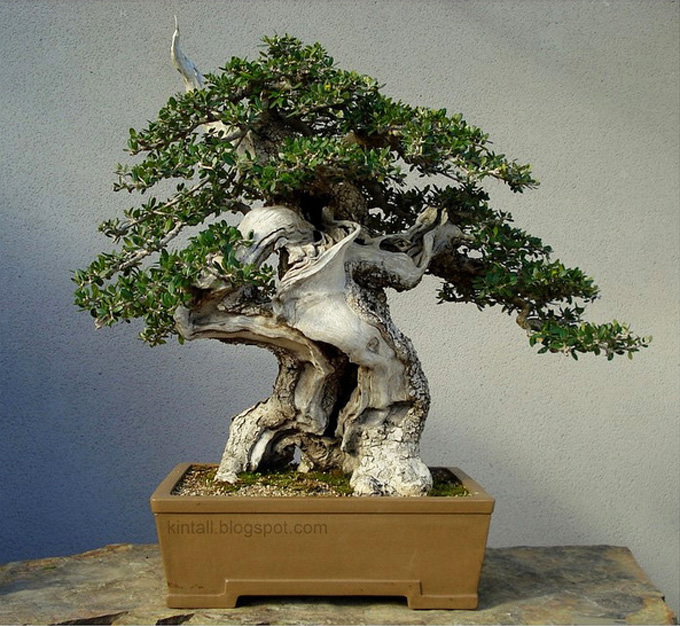

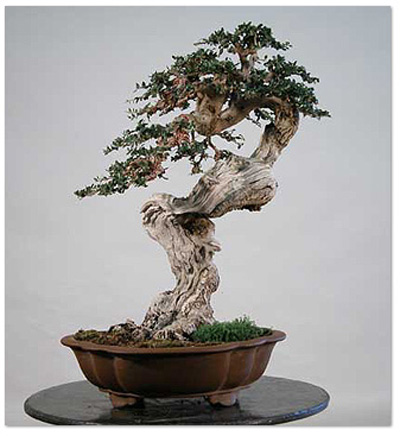

Full cascade Scot’s pine by David Benavente. You can provide the adjectives.  A wild looking Wild olive.

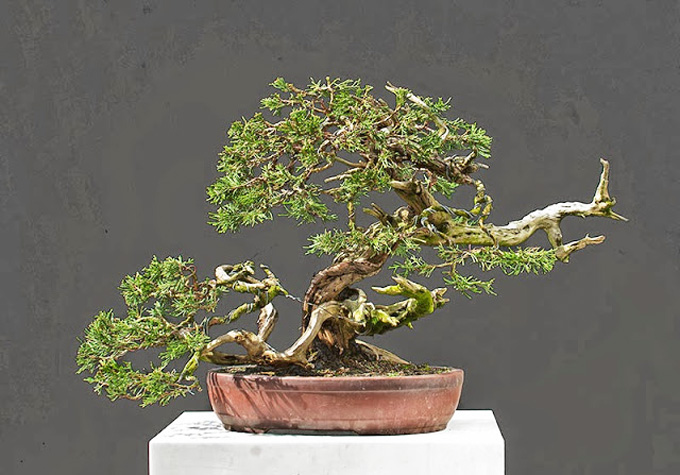

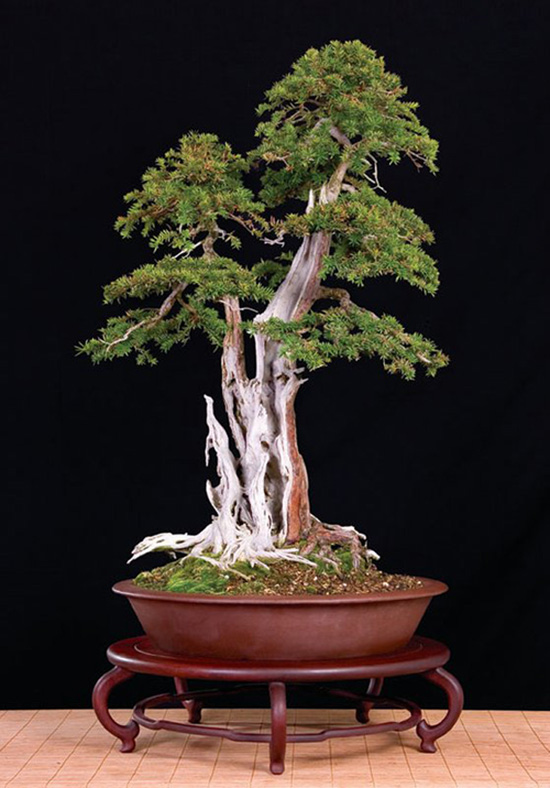

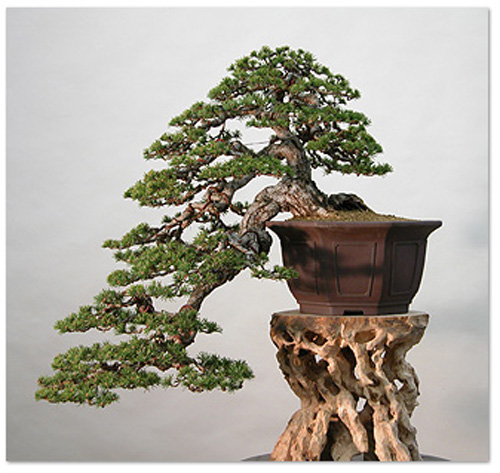

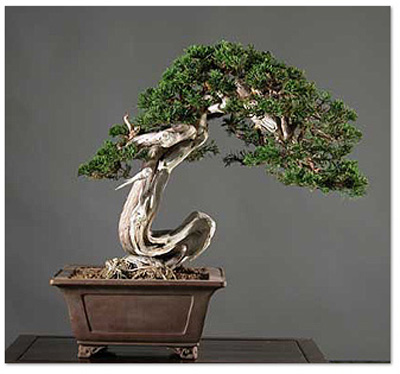

A wild looking Wild olive. Savin juniper (BTW we just devoted

Savin juniper (BTW we just devoted