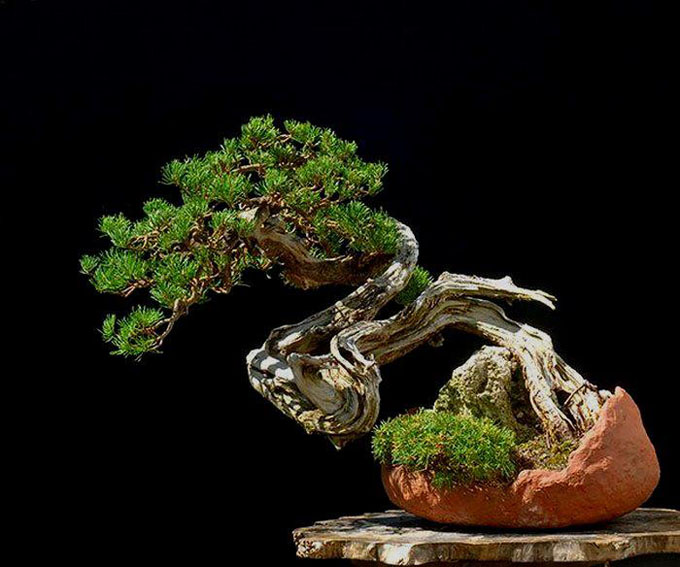

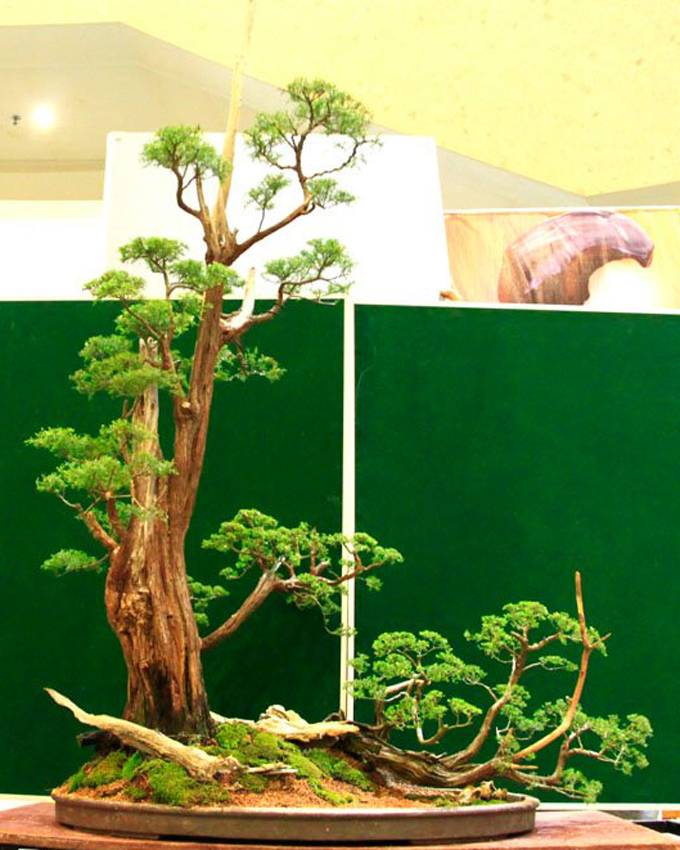

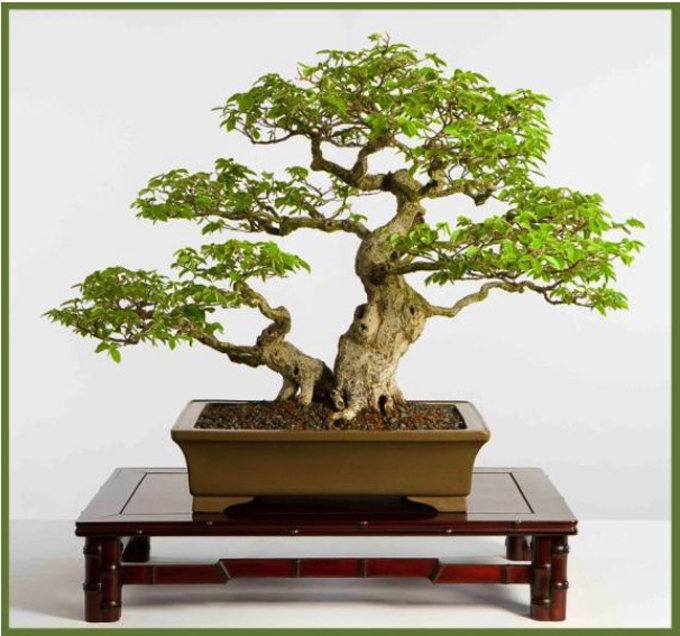

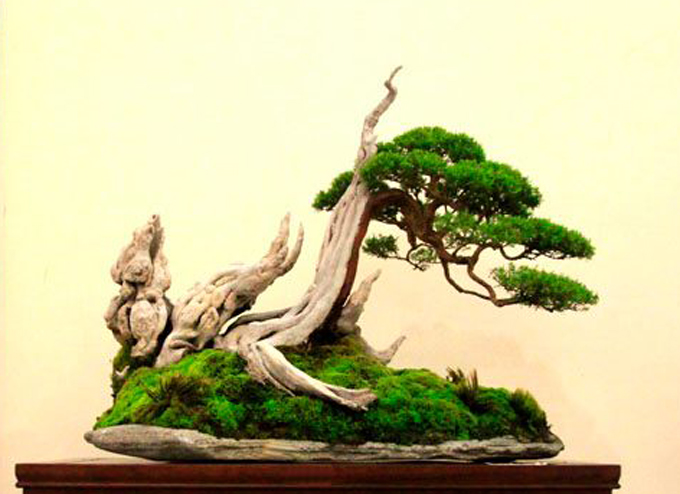

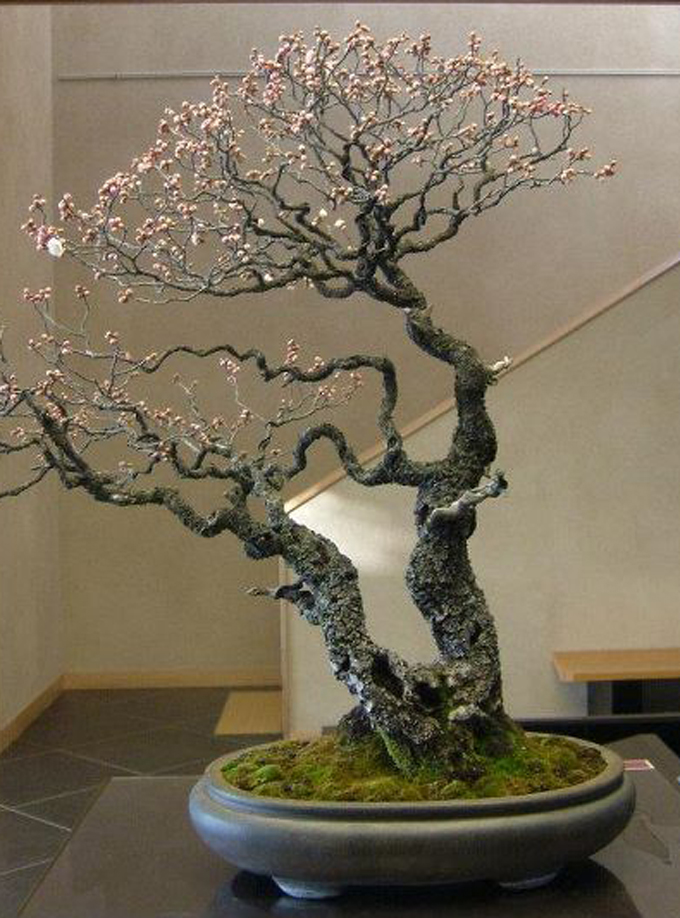

Sabamiki and uro. Aside from its overall power and beauty, there are a several things that might catch your eye: the flowers and buds, the aged bark (Ume bark develops an aged look fairly fast) and the hollowed out trunk (sabamiki). If you look closely you can also see several uro (small hollows that are left on deciduous trees where branches have rotted and fallen off, though bonsai uro may well be man made).

Sabamiki and uro. Aside from its overall power and beauty, there are a several things that might catch your eye: the flowers and buds, the aged bark (Ume bark develops an aged look fairly fast) and the hollowed out trunk (sabamiki). If you look closely you can also see several uro (small hollows that are left on deciduous trees where branches have rotted and fallen off, though bonsai uro may well be man made).

What’s in a name?

Ume have several names: Prunus mume (or just mume), Japanese apricot (or sometimes Japanese flowering apricot) and Chinese plum to name the most common. In the bonsai world, Ume seems to be the name of choice.

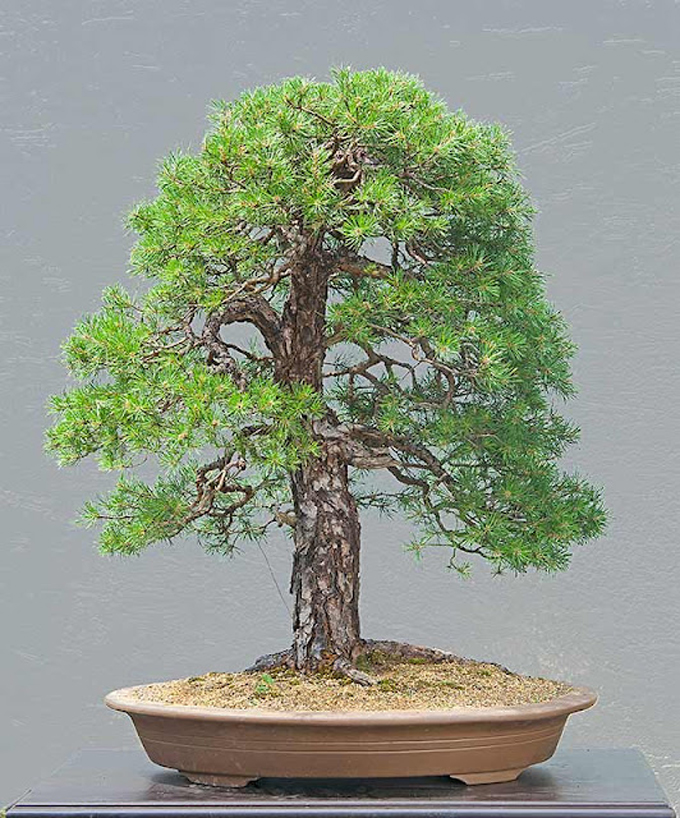

Fantastic bonsai

Ume is an Asian native and even though they make fantastic bonsai, for some reason not many nurseries grow them here in North America (Muranaka Nursery on the California central coast is one exception). As far as I know, they aren’t that difficult to grow as bonsai and they have numerous positive traits: they show the appearance of great age while still fairly young, they combine graceful elegance and tough looking ruggedness, and offer a striking display of buds and flowers late each winter. Altogether a noble candidate for your bonsai collection.

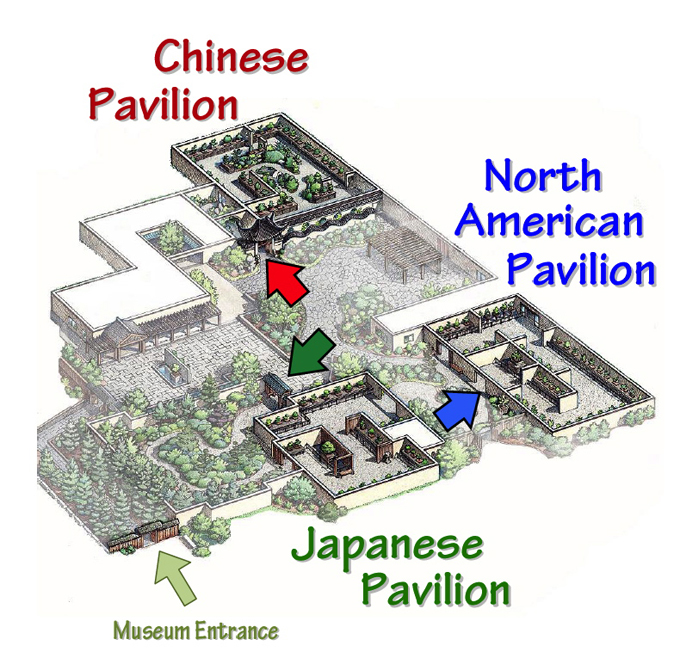

Omiya Bonsai Art Museum

The trees shown here reside at the Omiya Bonsai Art Museum in Saitama City, Japan. The photos are from Yoshitomo Ishizuka’s facebook page.

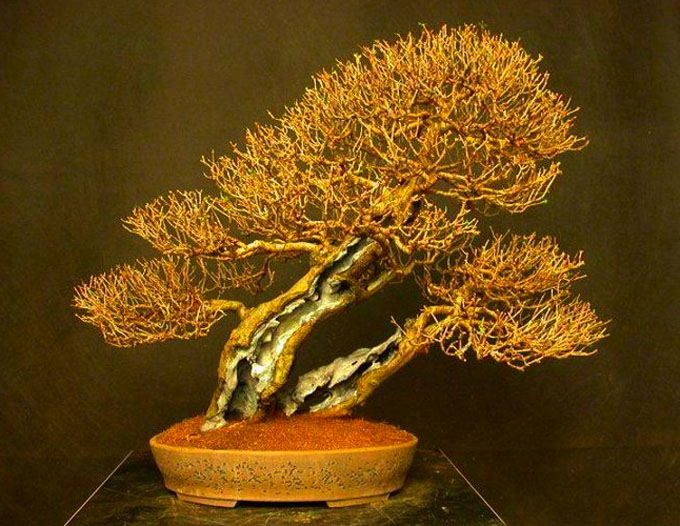

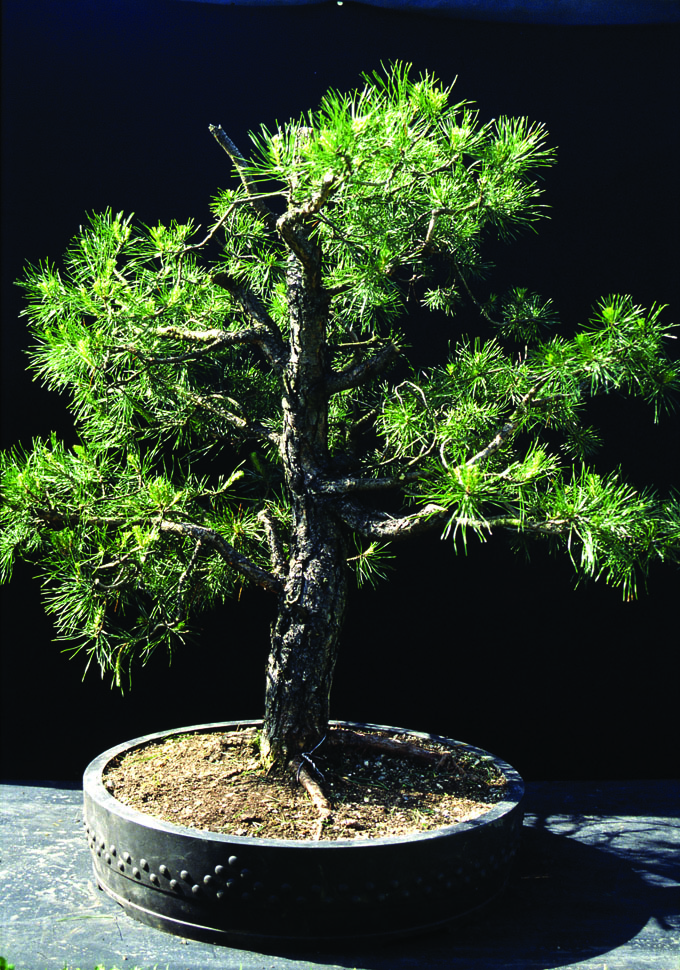

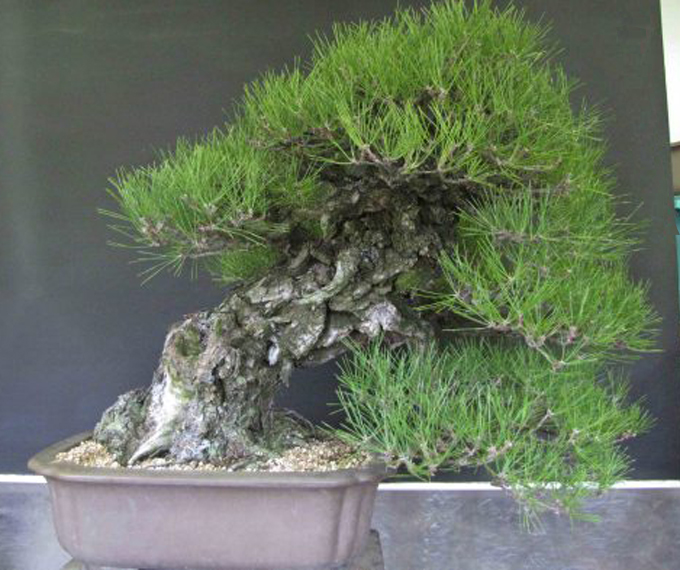

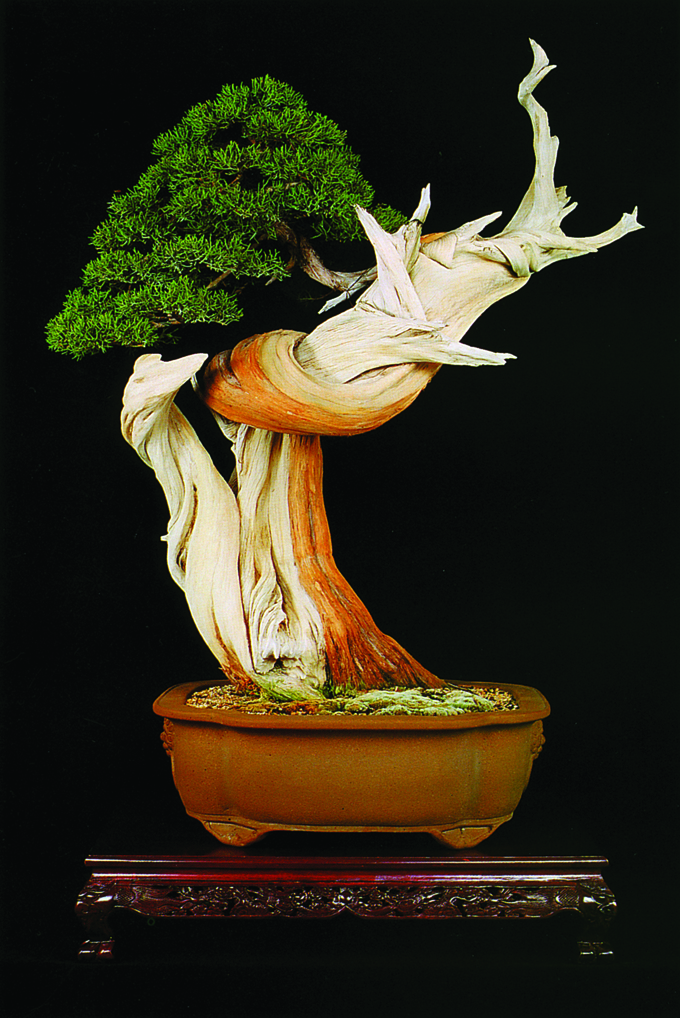

Shari. Though it’s a little difficult to see, this ume features some deadwood (shari) on the trunk. You usually see deadwood on conifers, as it tends to rot fairly quickly on deciduous trees. However, on ume deadwood rots quite slowly, so the shari on this tree appears natural.

Shari. Though it’s a little difficult to see, this ume features some deadwood (shari) on the trunk. You usually see deadwood on conifers, as it tends to rot fairly quickly on deciduous trees. However, on ume deadwood rots quite slowly, so the shari on this tree appears natural.

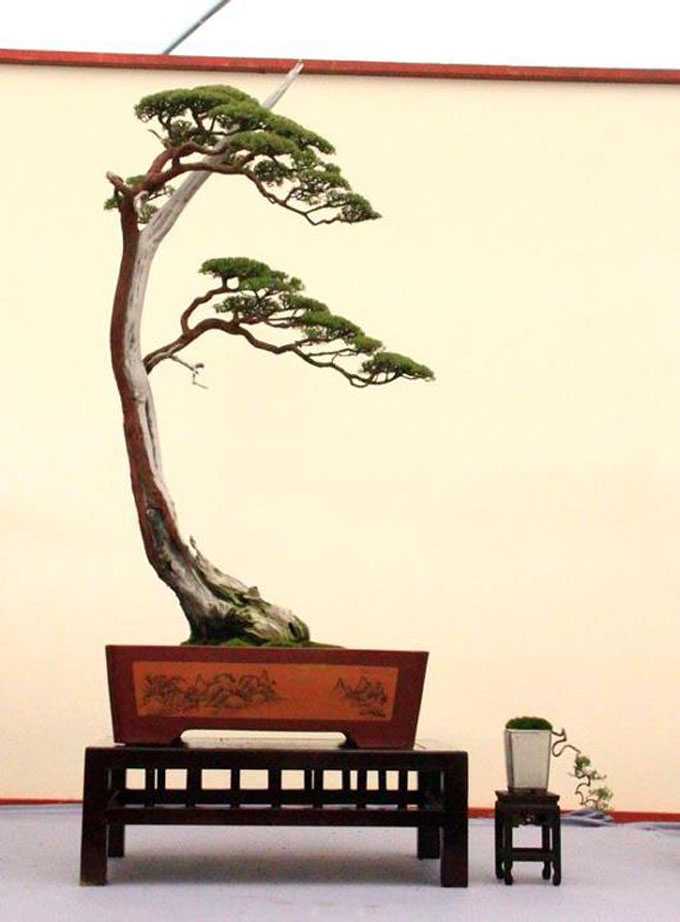

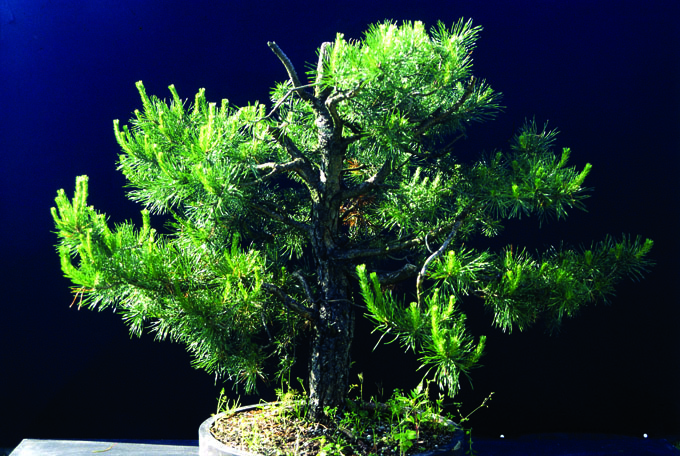

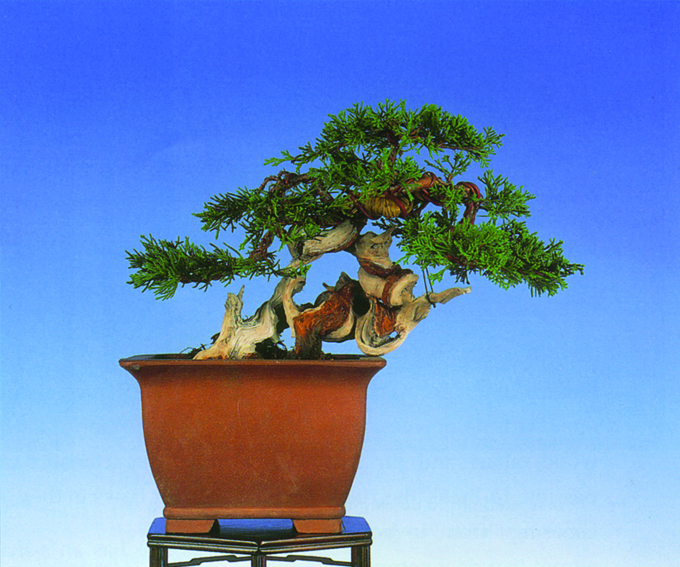

Fluid motion. Ume trunks and branches tend to display graceful, fluid motion. Just one more feature that makes Ume such a great subject for bonsai.

Fluid motion. Ume trunks and branches tend to display graceful, fluid motion. Just one more feature that makes Ume such a great subject for bonsai.